BY ORDER OF THE SECRETARY

OF THE AIR FORCE

AIR FORCE MANUAL 65-506

6 SEPTEMBER 2019

Financial Management

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS

COMPLIANCE WITH THIS PUBLICATION IS MANDATORY

ACCESSIBILITY: Publications and forms are available on the e-Publishing website at

www.e-Publishing.af.mil for downloading or ordering

RELEASABILITY: There are no releasability restrictions on this publication

OPR: SAF/FMCE

Supersedes: AFMAN 65-506, 29 August 2011

AFMAN 65-510, 19 October 2010

Certified by: SAF/FMC

(Ms. Pamela C. Schwenke)

Pages: 166

This manual implements Air Force Instruction (AFI) 65-501, Economic Analysis, by providing

information on applying the Economic Analysis (EA) approach to support Air Force decisions.

This publication applies to all civilian employees and uniformed members of the Regular Air

Force, the Air Force Reserve and the Air National Guard. Ensure all records created as a result of

processes prescribed in this publication are maintained in accordance with Air Force Manual

(AFMAN) 33-363, Management of Records, and disposed of in accordance with the Air Force

Records Disposition Schedule located in the Air Force Records Information Management System.

Refer recommended changes and questions about this publication to the Office of Primary

Responsibility (OPR) using AF Form 847, Recommendation for Change of Publication; route AF

Forms 847 from the field through the appropriate functional’s chain of command. The authorities

to waive wing/unit level requirements in this publication are identified with a Tier (“T-0, T-1, T-

2, T-3”) number following the compliance statement. See AFI 33-360, Publications and Forms

Management, for a description of the authorities associated with the Tier numbers. Submit requests

for waivers through the chain of command to the appropriate Tier waiver approval authority, or

alternately, to the Publication OPR for non-tiered compliance items. This publication may be

supplemented at any level, but all direct Supplements must be routed to the OPR of this publication

for coordination prior to certification and approval. The use of the name or mark of any specific

manufacturer, commercial product, commodity, or service in this publication does not imply

endorsement by the Air Force.

2 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

SUMMARY OF CHANGES

This manual combines AFMANs 65-506, Economic Analysis, and 65-510, Business Case Analysis

Procedures. This manual clarifies that economic analysis is both an analytical approach to

decision-making and one of many products resulting from the analytical approach. This manual

includes a clarification that all Comparative Analysis products (e.g., Economic Analysis (EA),

Cost Benefit Analysis, Analysis of Alternatives (AoA), Business Case Analysis (BCA)) fit under

the umbrella of the economic analysis approach and are subject to this instruction (consistent with

Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI) 7041.03, Economic Analysis for Decision Making).

This manual clarifies that the level of rigor in an economic analysis will vary with multiple factors

(e.g., maturity of the project, dollar value of the project)

This manual updated and added detail to the elements that must be addressed as part of the

economic analysis approach. This manual includes an economic analysis process overview with

tips on how to get started.

This AFMAN revised the chapter contents to more closely align with the elements that must be

included in a comparative analysis. Chapter 2 was expanded to include: Background, Scope, Facts

and Ground Rules. The Objective and Assumptions sections of Chapter 2 were clarified.

This manual made the instruction on alternatives into its own Chapter (Chapter 3). The Chapter

expands upon the previous explanation of alternatives.

This manual expands the Chapter on cost (Chapter 4) to include more information on building the

cost analysis. Chapter 4 includes a table to explain the different purposes of cost estimates and

provide the context of how building the cost estimates for a comparative analysis differs from other

cost estimates. Chapter 4 explains the incremental cost concept. Chapter 4 includes the basic steps

for building a cost estimate and a brief description of a few common estimating techniques.

Chapter 4 moved topics such as terminal value, discount factors, present value, and Uniform

Annual Cost method to the section on “Other Considerations in the Cost Analysis.”

The chapter on benefits (Chapter 5) now includes more information on building a benefit analysis.

Chapter 5 added flexibility to allow for benefits to be expressed as either a narrative or on an

ordinal scale. Chapter 5 includes more detail on developing a benefit hierarchy (if needed) and

weighting benefits. Chapter 5 includes examples of benefit analysis summary tables.

The chapter on Uncertainty Analysis (sensitivity and risk analysis) (Chapter 6) now includes more

information on building risk and sensitivity analyses. Chapter 7 now includes comparison of

alternatives, providing results, documentation and post analysis activities. This chapter includes a

requirement to provide an interpretation of results. The post analysis activities include such topics

as: an implementation plan and stakeholder analysis. This manual moved special analyses to the

attachments and expanded them. This manual updated the attachments to include a section on the

Clinger-Cohen Act analyses (Attachment 13) and a section on Real Property Construction and

Repair analyses (Attachment 11).

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 3

This manual moved the Economic Impact Analysis (EIA) to Attachment 12. The attachment was

changed to adapt to the new source of multipliers. This update includes references to a new Excel

Tool that implements the new method for performing the economic impact analysis.

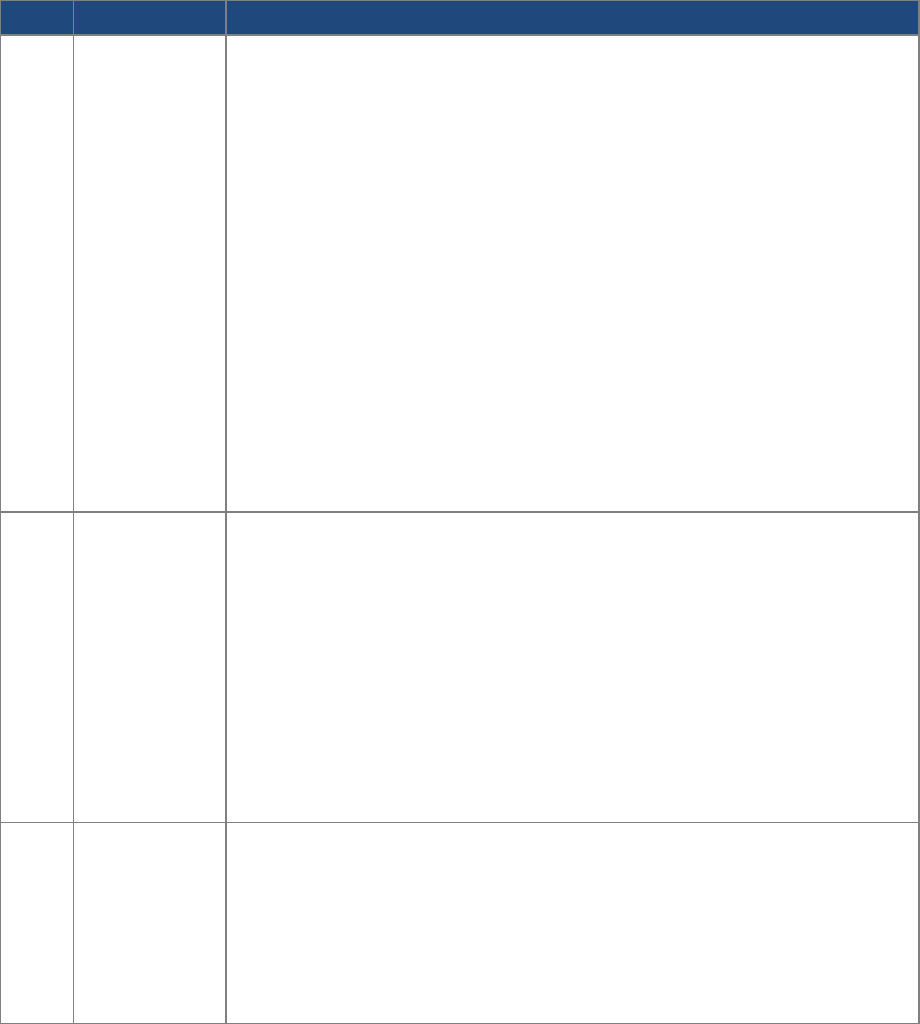

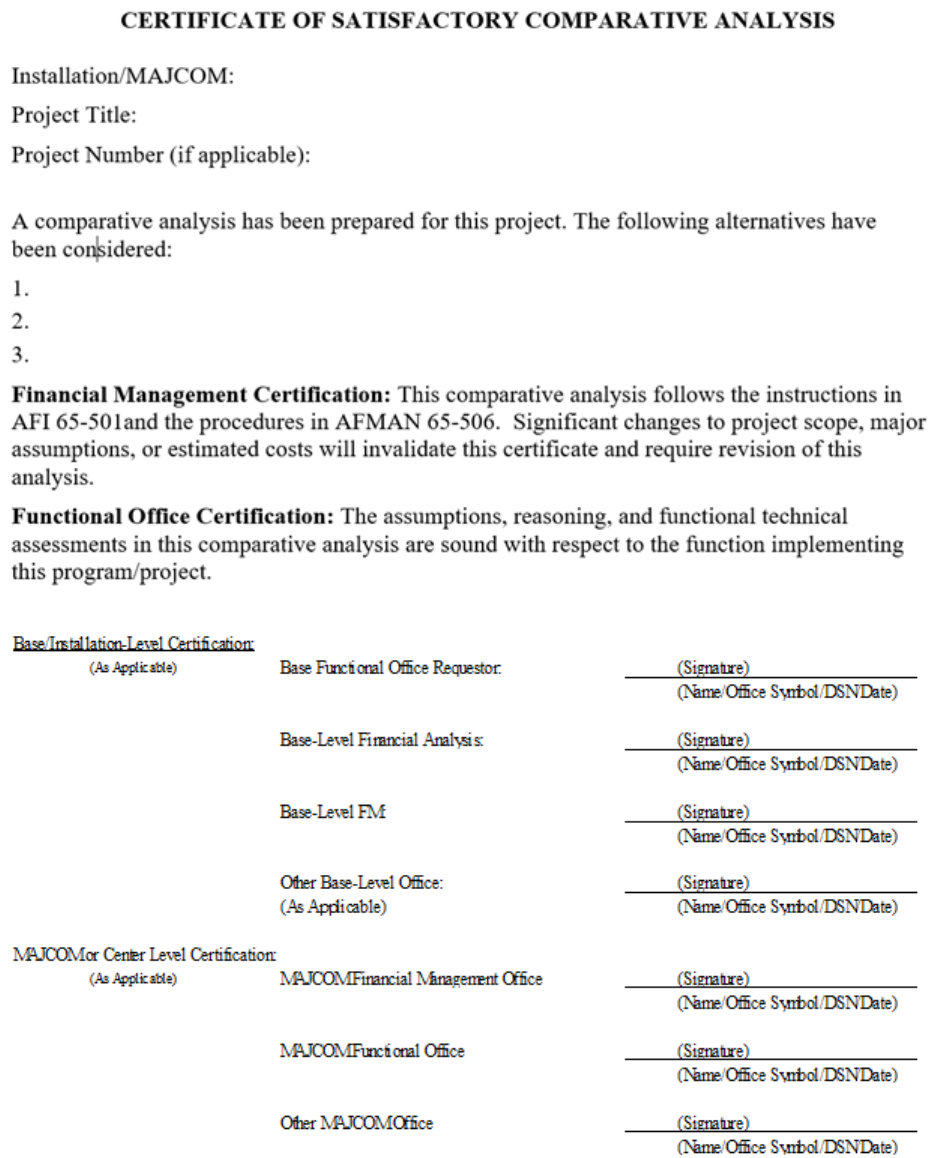

This manual updates the form for submitting a waiver and the format for the Executive Summary.

This manual added information on the certification process that includes consideration of recent

changes to Air Force organizations. This manual also updated the certificate of satisfactory

economic analysis.

This manual updated the Economic Analysis Review Guide (Attachment 6), and the Preparer’s

Guides (Attachment 5). This manual updated the formulas for Factors and financial Indicators

(Attachment 7).

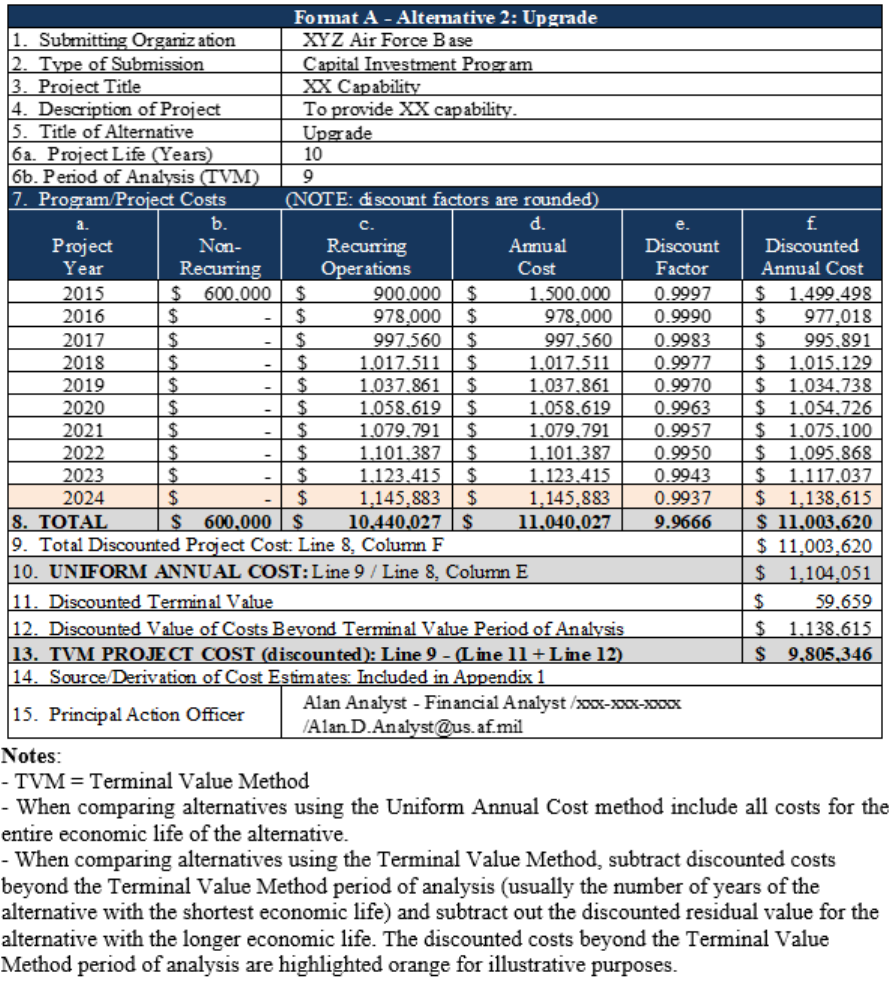

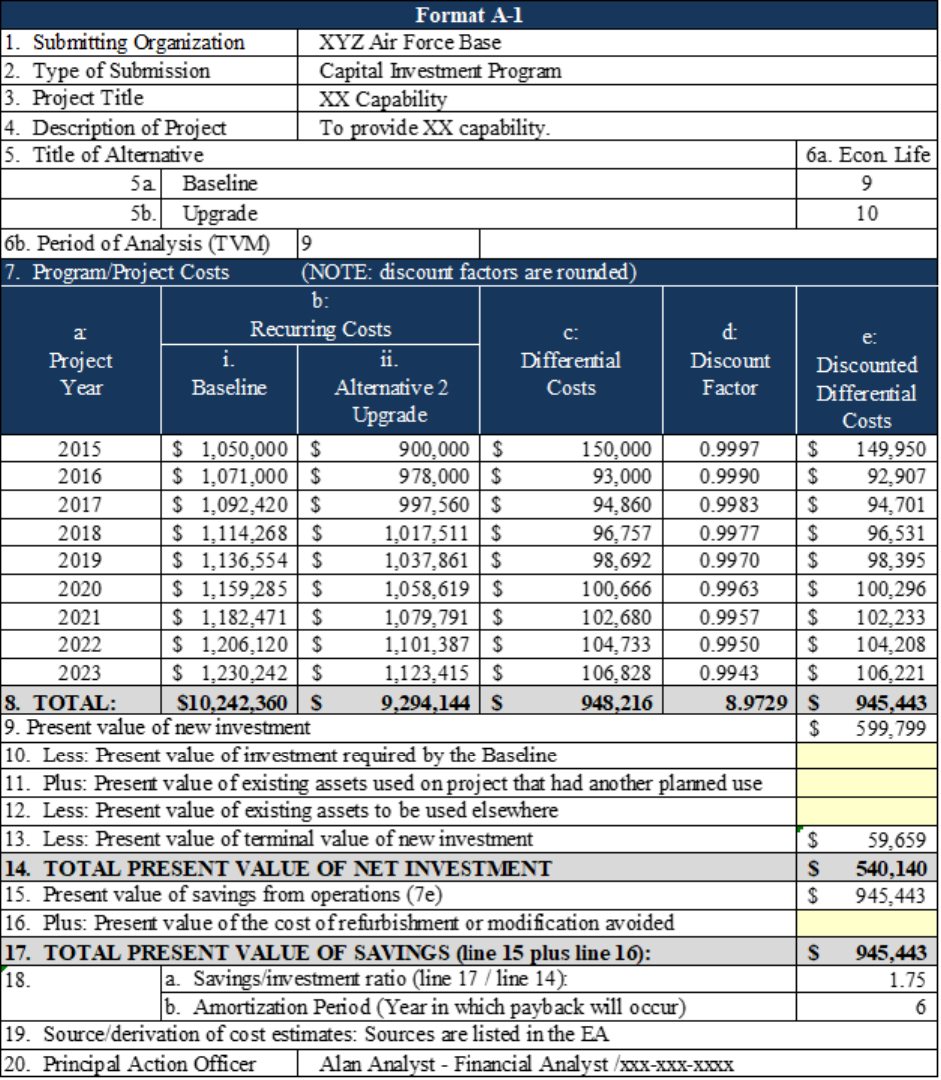

This manual updates the sample formats for summary of costs (Format A and Format A-1)

(Attachment 8). The update clarifies which costs should be included when using the Uniform

Annual Cost Method versus the Terminal Value Method.

Chapter 1— ECONOMIC ANALYSIS PRINCIPLES 7

1.1. Economic Analysis Background ............................................................................. 7

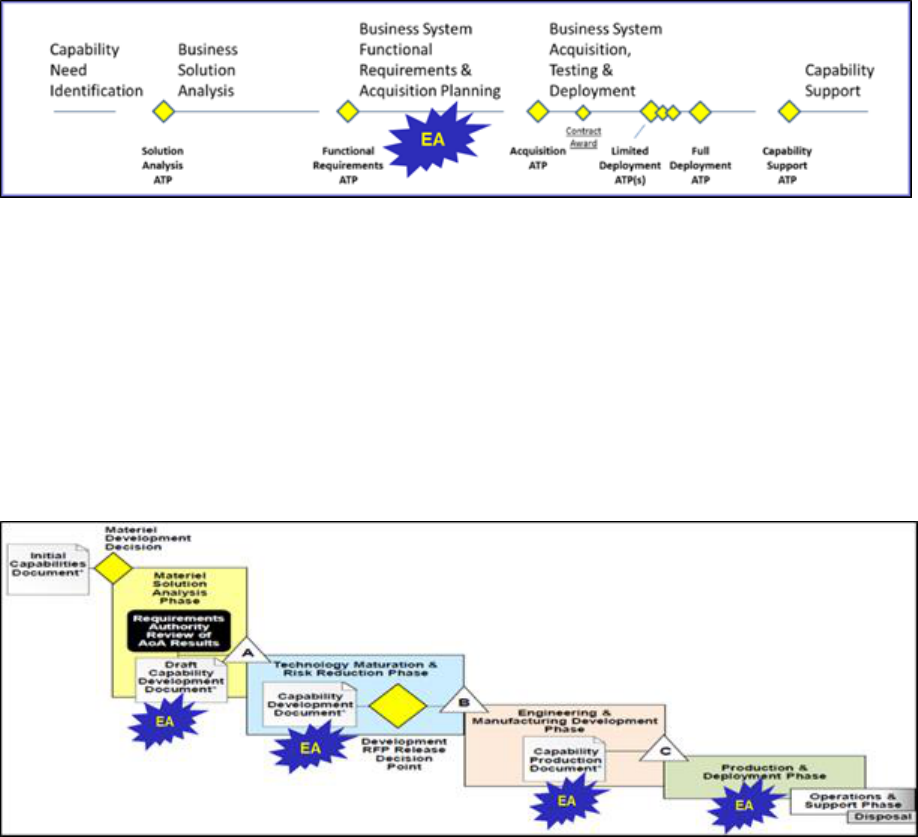

Figure 1.1. Economic Analysis Approach and Comparative Analysis. .................................... 7

1.2. Elements of the Economic Analysis Approach....................................................... 8

1.3. Applying the Economic Analysis Approach: Overview. ........................................ 9

Figure 1.2. Comparative Analysis Support. .............................................................................. 10

Figure 1.3. Foundational Elements. .......................................................................................... 11

Figure 1.4. Data Collection. ...................................................................................................... 11

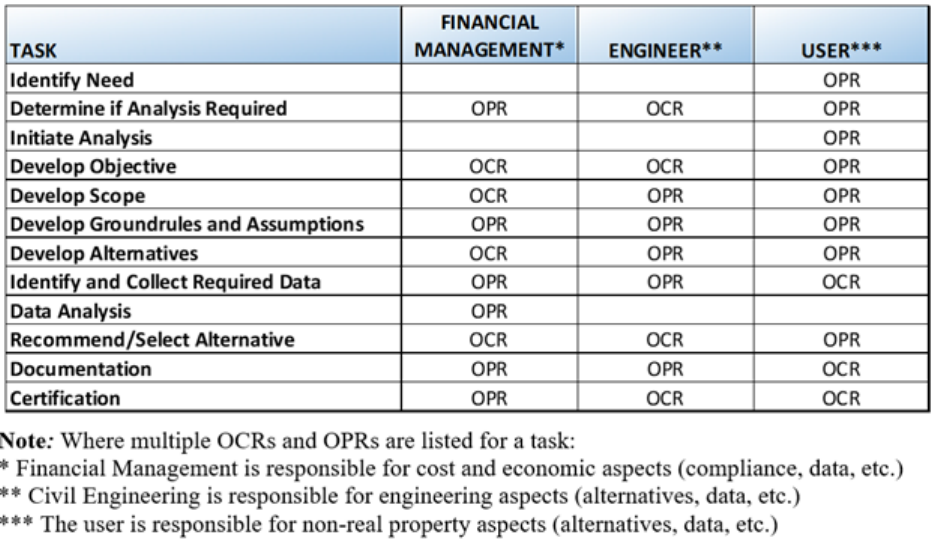

1.4. Roles and Responsibilities. ................................................................................... 11

Chapter 2— FOUNDATIONAL ELEMENTS: BACKGROUND, OBJECTIVE, SCOPE,

FACTS, GROUND RULES AND ASSUMPTIONS 12

2.1. Background. .......................................................................................................... 12

2.2. Objective of the Comparative Analysis. ................................................................ 12

Figure 2.1. Objective. ................................................................................................................ 13

2.3. Scope. ..................................................................................................................... 13

2.4. Parameters of the Analysis (Facts/Ground Rules/Assumptions). ......................... 13

Chapter 3— ALTERNATIVES 15

3.1. Overview. ................................................................................................................ 15

4 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

3.2. Baseline/Status Quo ................................................................................................ 15

3.3. Reasonableness and Feasibility............................................................................... 15

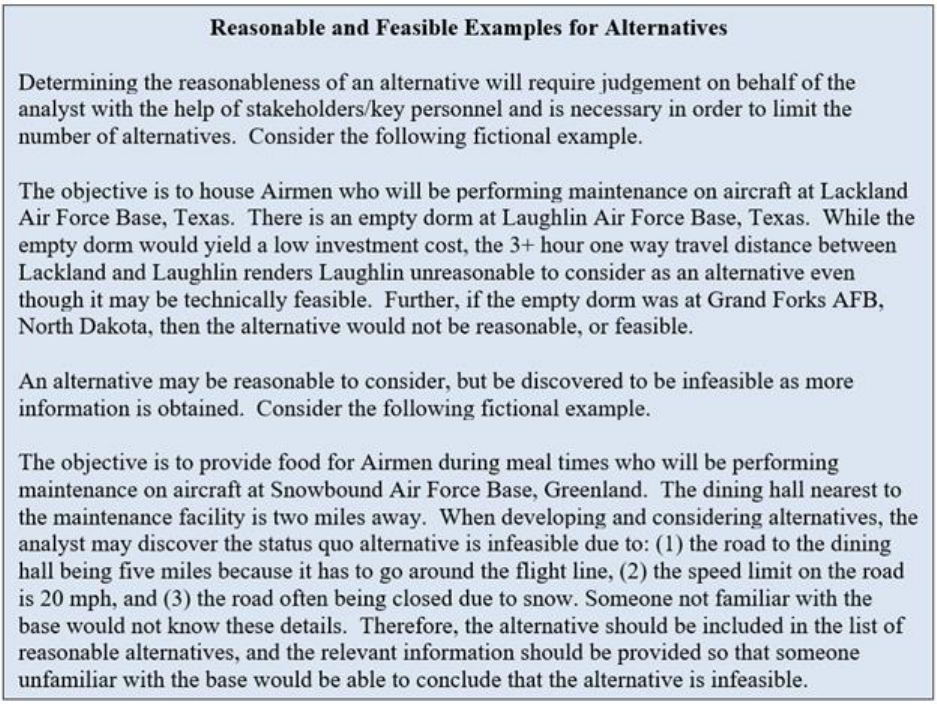

Figure 3.1. Reasonable and Feasible Examples for Alternatives. ............................................. 16

Figure 3.2. Reasonable and Feasible Notional Illustration........................................................ 17

3.4. Completeness .......................................................................................................... 17

3.5. Describing Alternatives .......................................................................................... 17

Chapter 4— COST ANALYSIS 19

4.1. Overview - Cost Analysis ....................................................................................... 19

4.2. Purpose of Cost Analysis ....................................................................................... 19

Table 4.1. Cost and Purpose. ................................................................................................... 19

4.3. Basic Steps for the Cost Analysis ........................................................................... 20

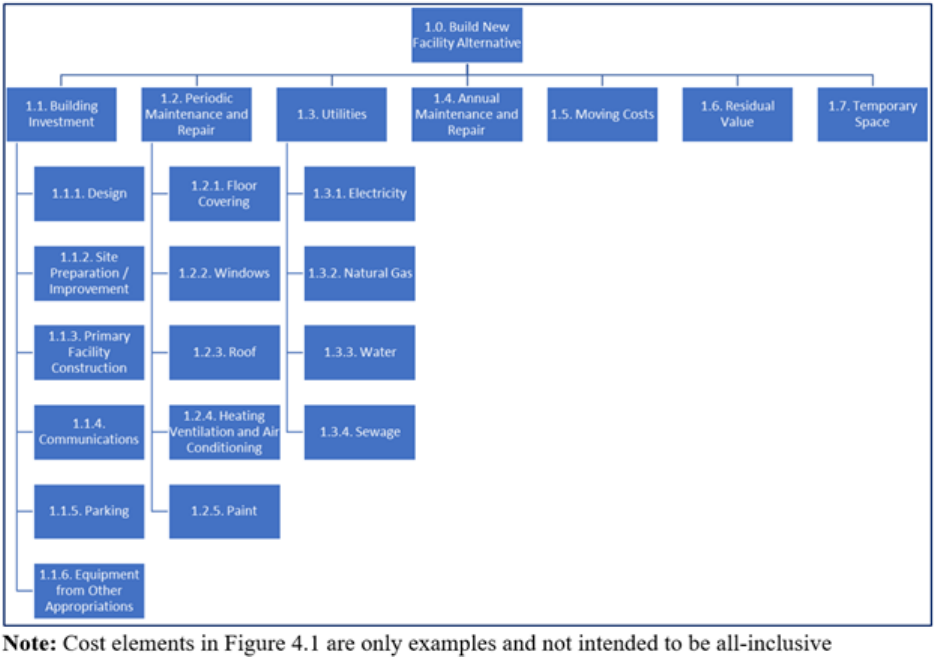

Figure 4.1. Example - Build New Facility Cost Element Structure. ......................................... 21

4.4. Components of a Cost Analysis .............................................................................. 23

4.5. Other Considerations in the Cost Analysis ............................................................. 27

Figure 4.2. Incremental Cost Example. ..................................................................................... 29

Chapter 5— BENEFIT ANALYSIS 32

5.1. Overview – Benefit Analysis .................................................................................. 32

5.2. Role of Benefits ...................................................................................................... 32

5.3. Types of Benefits .................................................................................................... 32

5.4. Basic Steps for Benefit Analysis............................................................................. 34

Figure 5.1. Quantifying Benefits. .............................................................................................. 37

Figure 5.2. Benefit Weighting Example. ................................................................................... 38

Figure 5.3. Relative Ranking without Weights. ........................................................................ 39

Figure 5.4. Relative Ranking with Weights. ............................................................................. 40

Figure 5.5. Weighted Benefits Score Evaluated at a Summary Level. ..................................... 41

Figure 5.6. Benefits Evaluated as a Hierarchy. ......................................................................... 42

5.5. Other Benefit Considerations .................................................................................. 43

Chapter 6— UNCERTAINTY (RISK AND SENSITIVITY) ANALYSIS 44

6.1. Uncertainty Analysis Overview .............................................................................. 44

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 5

6.2. Sensitivity Analysis ................................................................................................ 44

6.3. Risk Analysis .......................................................................................................... 45

Figure 6.1. Risk Matrix Example. ............................................................................................. 47

Figure 6.2. Definitions for Likelihood Categories. ................................................................... 47

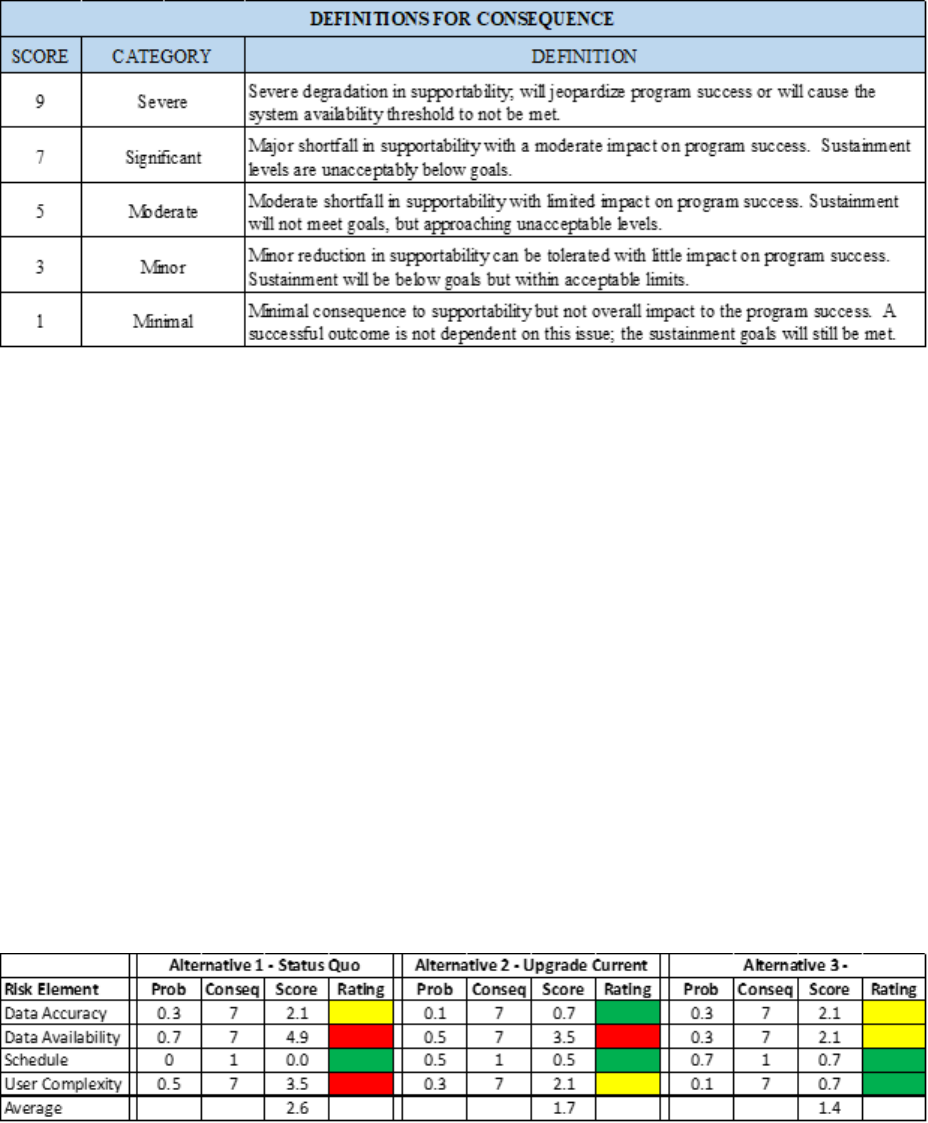

Figure 6.3. Definitions for Consequence Categories. ............................................................... 48

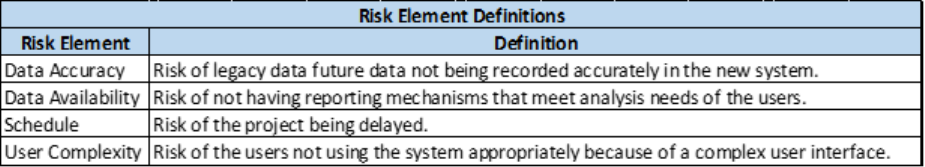

Figure 6.4. Summary of Risk Analysis. .................................................................................... 48

Figure 6.5. Risk Element Definitions. ....................................................................................... 49

Chapter 7— CONCLUDING THE ANALYSIS: SUMMARY AND COMPARISON OF

ALTERNATIVES AND POST-ANALYSIS ACTIVITIES 50

7.1. Once the cost, benefit and uncertainty analyses are completed for each

alternative: .............................................................................................................. 50

7.2. Provide summary tables for: .................................................................................. 50

7.3. Provide a brief narrative explanation of: ............................................................... 50

7.4. Every comparative analysis must: ......................................................................... 50

7.5. If the analyst provides a recommendation: ............................................................ 51

7.6. The decision-maker at each level may: .................................................................. 51

7.7. Documentation Requirements. ............................................................................... 51

7.8. Information and Activities that are Important for Implementing a Decision .......... 52

Chapter 8— ANNUAL ECONOMIC ANALYSIS REPORT 53

8.1. Annual Economic Analysis Report (RCS: HAF-FMC [A] 9501): ........................ 53

Attachment 1— GLOSSARY OF REFERENCES AND SUPPORTING INFORMATION 54

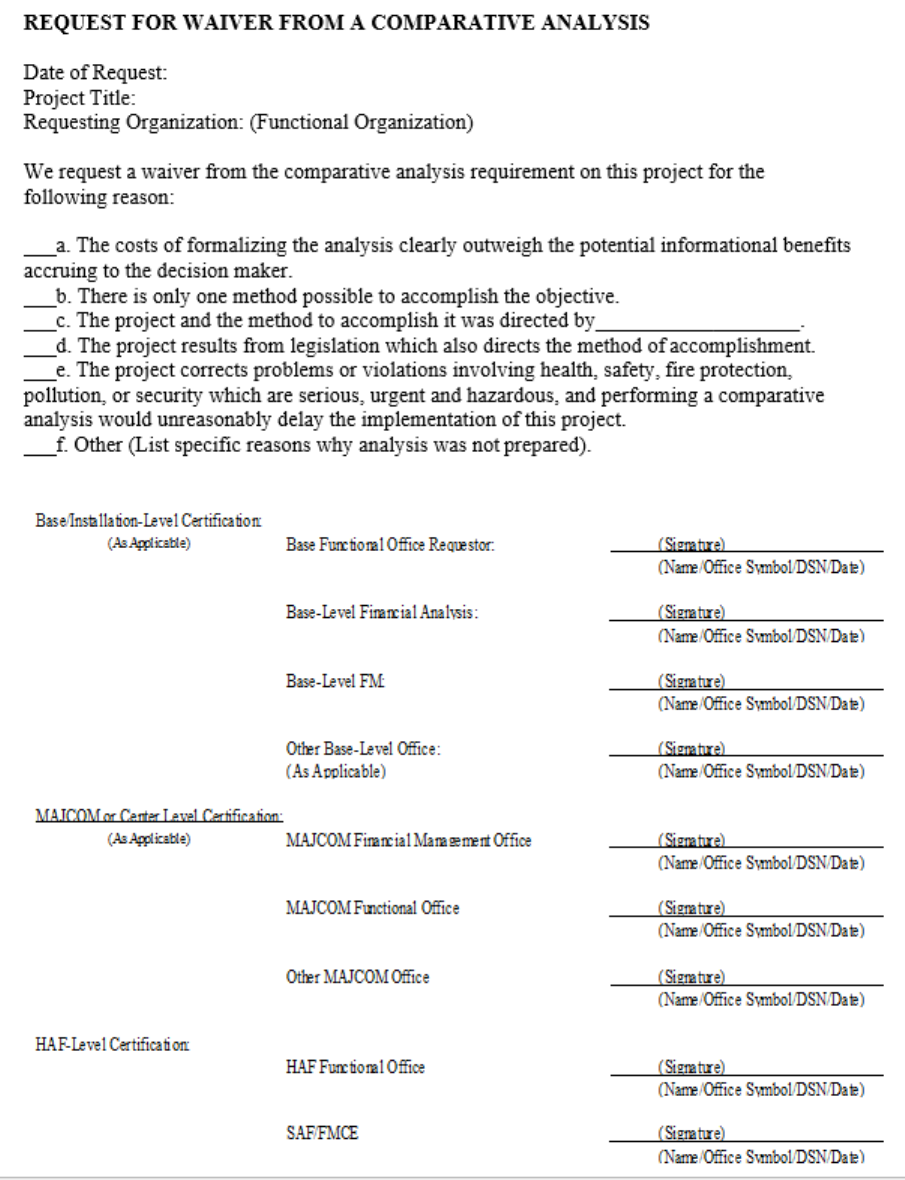

Attachment 2— EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FORMAT REQUIREMENT 61

Attachment 3— COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS CERTIFICATION AND WAIVER

APPROVAL 63

Attachment 4— REQUEST FOR WAIVER FROM THE COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS

REQUIREMENT 74

Attachment 5— COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS PREPARER’S GUIDE 76

Attachment 6— COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS REVIEWER/CERTIFICATION GUIDE 85

Attachment 7— FORMULAS FOR FACTORS AND FINANCIAL INDICATORS 98

Attachment 8— SAMPLE FORMATS FOR SUMMARY OF COSTS 103

6 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

Attachment 9— PRELIMINARY COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 109

Attachment 10— ANNUAL ECONOMIC ANALYSIS REPORT (RCS: HAF-FMC[A]

9501) FORMAT 111

Attachment 11— REAL PROPERTY CONSTRUCTION AND REPAIR ECONOMIC

ANALYSES 112

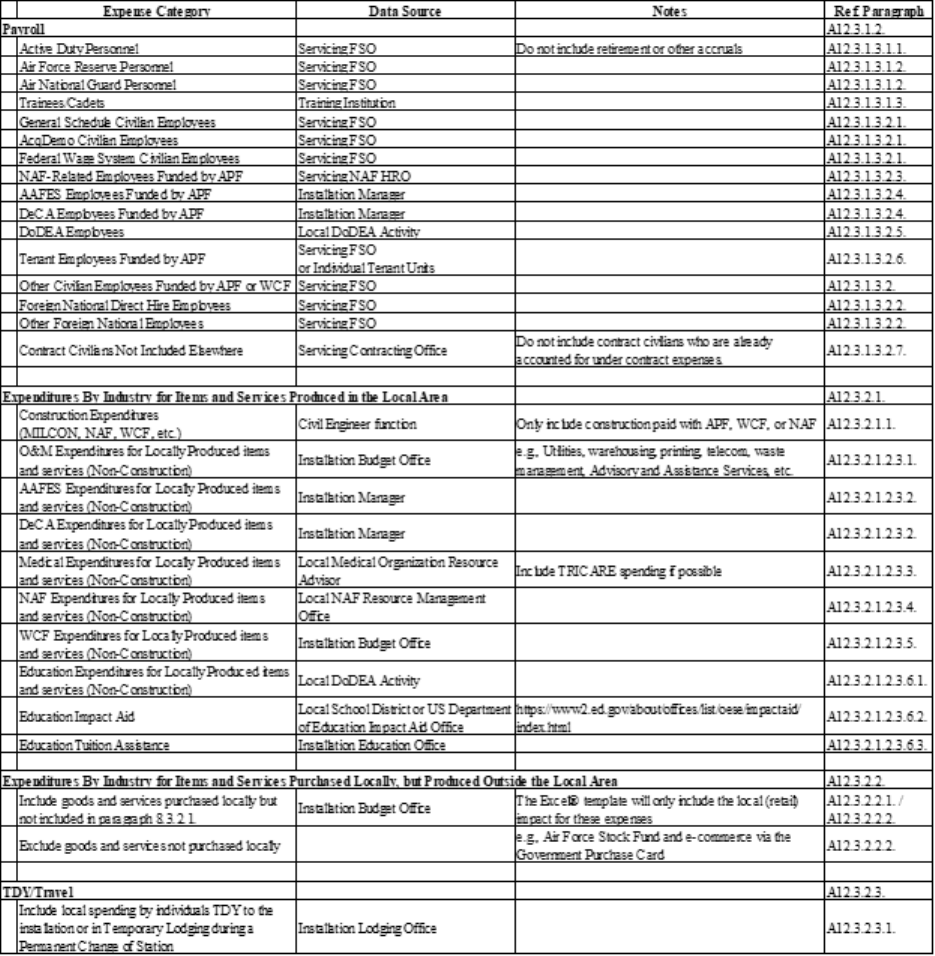

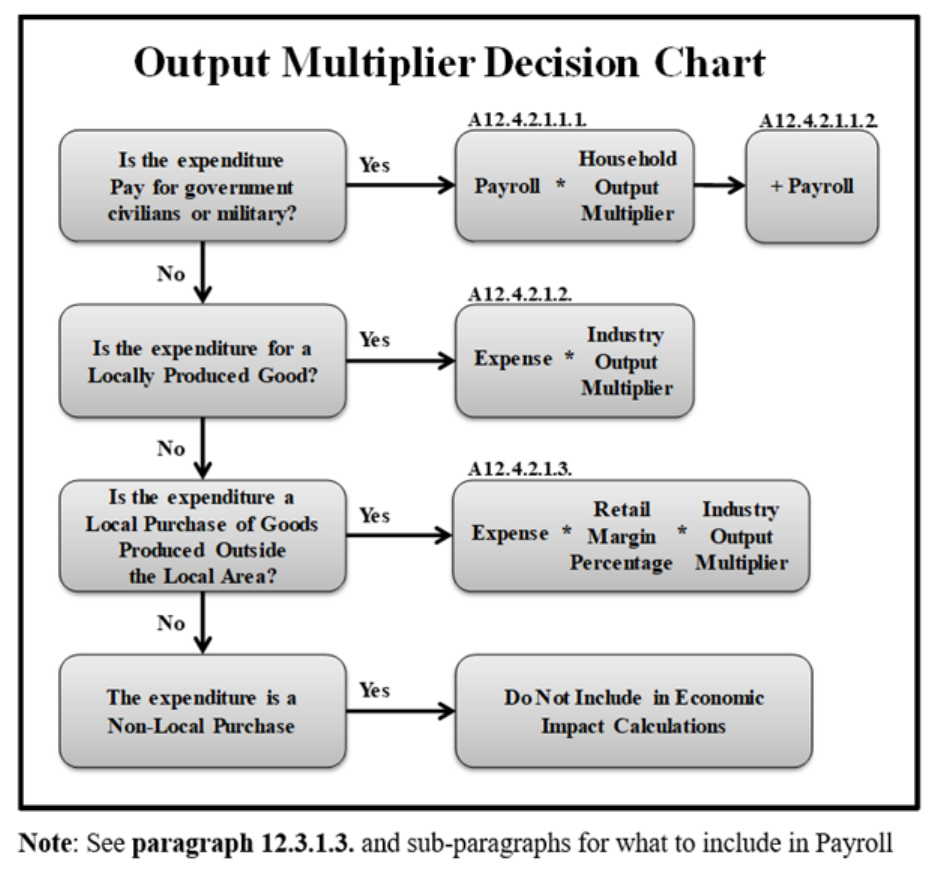

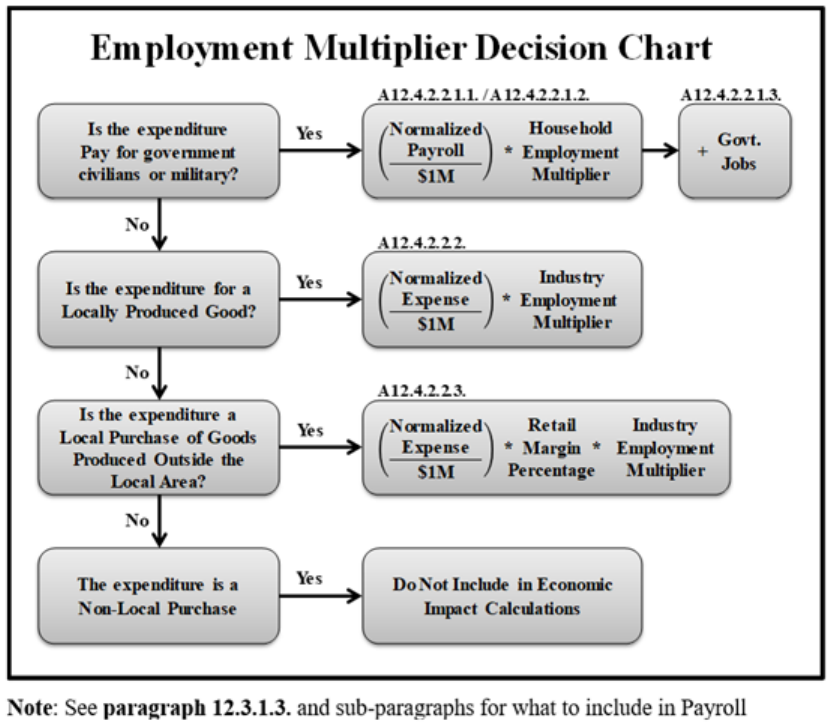

Attachment 12— ECONOMIC IMPACT ANALYSIS 139

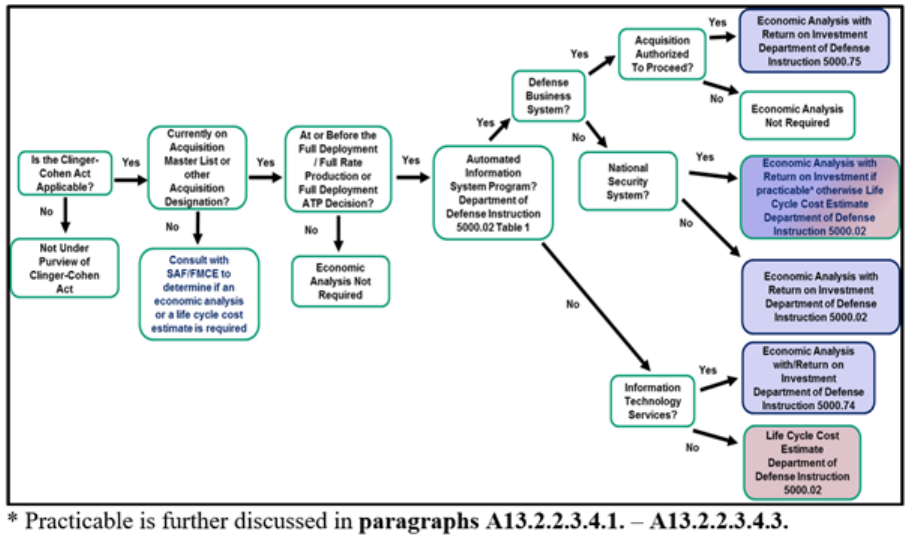

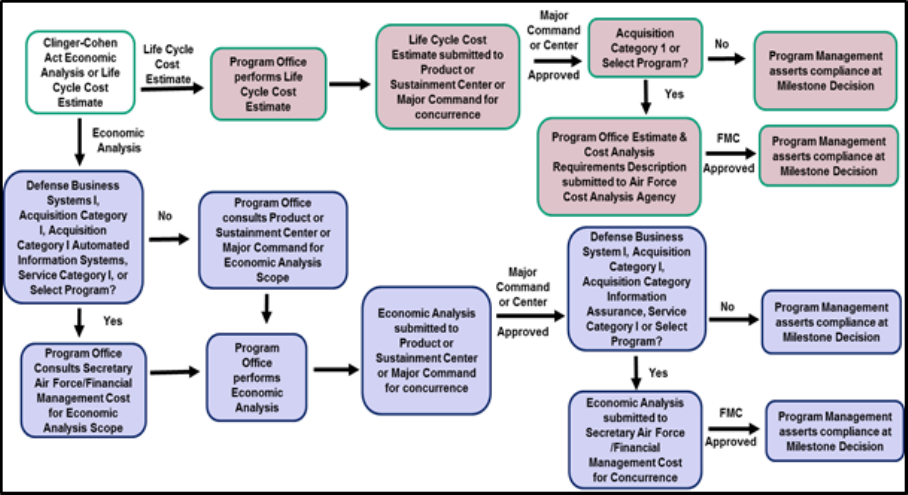

Attachment 13— CLINGER-COHEN ACT ECONOMIC ANALYSES 151

Attachment 14— OTHER SPECIALIZED ANALYSES 159

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 7

Chapter 1

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS PRINCIPLES

1.1. Economic Analysis Background

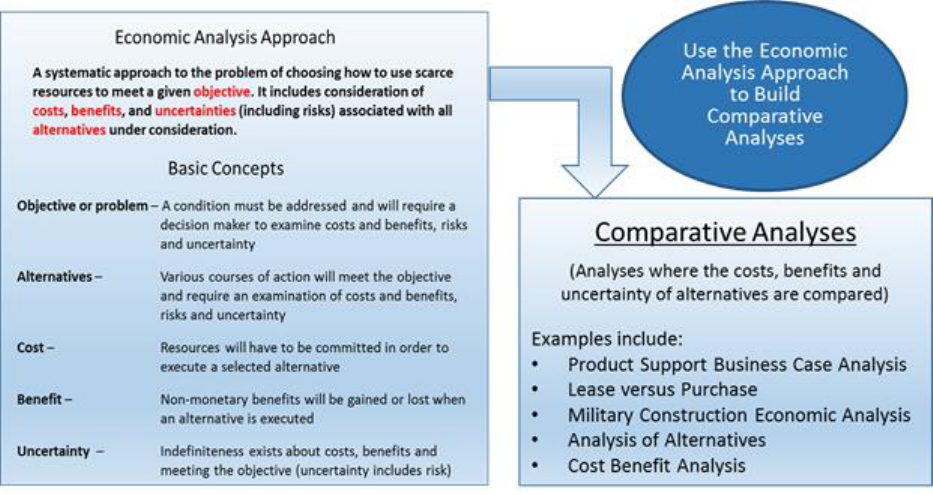

1.1.1. Economic analysis is a systematic approach to decide how to use scarce resources to

meet a given objective. Properly using the economic analysis approach yields an impartial

analysis of competing alternatives to meet an objective, and weighs the costs, and benefits and

uncertainty for each alternative. The economic analysis approach does not replace the

judgment of a decision maker, but rather provides an analytic and uniform foundation upon

which sound decisions can be made.

1.1.2. Analyses that include costs and benefits to support decision making are performed under

a variety of names (e.g., Cost Benefit Analysis, Analysis of Alternatives, Economic Analysis,

Business Case Analyses). Any analysis that includes cost benefit and uncertainty

considerations fits under the definition of “economic analysis” even though not specifically

titled as such.

1.1.3. For the remainder of this manual, all analyses resulting from implementing the

economic analysis approach will be referred to as “comparative analyses” or simply as

“analyses” unless referring to a specific product whose name has been directed at a higher level

(e.g., Product Support Business Case Analysis, Military Construction Economic Analysis).

The conceptual approach to decision-making will be referred to as economic analysis to remain

consistent with DoDI 7041.03.

Figure 1.1. Economic Analysis Approach and Comparative Analysis.

1.1.4. The economic analysis approach considers all significant anticipated effects of a

decision across the entire organization, not just the financial ones. It also assesses the

likelihood that those effects will occur as anticipated (i.e., uncertainty/risk).

8 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

1.1.5. Programs, projects, and initiatives evaluated using the economic analysis approach may

include any significant decision that leadership is contemplating. The following is a sample

(not all-inclusive) list of programs and situations for which the economic analysis approach

can be used to assist in decision making:

1.1.5.1. Military construction (MILCON), military family housing and facility repair.

1.1.5.2. Tradeoffs between force structures, force size, modernization, fuel/energy

consumption, and readiness.

1.1.5.3. Manpower analysis.

1.1.5.4. Projects to mechanize, automate, prevent obsolescence, improve workflow and

layout, or increase capacity.

1.1.5.5. Acquiring, repairing, supporting, modifying or replacing weapon systems,

information systems or information technology.

1.1.5.6. Acquiring or upgrading equipment to reduce operating and support costs.

1.1.5.7. Lease or purchase of general purpose real property, such as office buildings,

warehouses, and associated land.

1.1.5.8. Consolidating facilities, such as warehouses, maintenance and storage depots, and

repair activities to decrease cost for any reason or to add to mission effectiveness.

1.1.5.9. Business process improvement (business reengineering).

1.2. Elements of the Economic Analysis Approach.

1.2.1. The economic analysis approach will be driven by the context around the decision.

Some of the drivers include: the stage a program or project is in its life cycle, the level of

resources consumed in the project, the level of visibility, and the scope/significance of the

objective. As a result, analysis may require a tailored approach to fit the project. Tailoring

could include abbreviating some elements of the analysis, or going into greater depth on some

elements, but in almost all cases the basic elements in 1.2.2 need to be included in some

manner.

1.2.2. Unless otherwise stated, the elements below must be included when applying the

economic analysis approach. (T-2).

1.2.2.1. Background/Objective/Scope – These areas provide the programmatic foundation

upon which the analysis is built. The background provides the context for the analysis while

the objective and scope define what the project or program under study seeks to attain.

1.2.2.2. Facts/Ground Rules/Assumptions – These areas identify parameters significant to

the analysis. Facts are key known parameters that are significant to the analysis. Ground

rules are general principles (often directive in nature) that provide bounds for the analysis.

Assumptions are key parameters where the values and circumstances must be estimated

because reliable knowledge is lacking. Without assumptions, analytical models would not

be able to produce useful conclusions.

1.2.2.3. Alternatives – Solution sets evaluated to meet the objective.

1.2.2.4. Cost Analysis – Analysis of monetary costs/savings/revenue effects by alternative.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 9

1.2.2.5. Benefit Analysis – Analysis of non-monetary attributes of each alternative.

1.2.2.6. Uncertainty Analysis

1.2.2.6.1. Sensitivity Analysis – Test of the assumptions to see how the results are

impacted.

1.2.2.6.2. Risk Analysis – Analysis of risks by alternative.

1.2.2.7. Summary and Comparison of Alternatives – Evaluation and comparison of the

alternatives and discussion of key findings in the analysis.

1.2.2.8. This list does not preclude an analyst from incorporating other relevant

information when using the economic analysis approach to complete a comparative

analysis.

1.2.3. The resulting comparative analysis product will be formatted with the following

sections: a certification (when required by AFI 65-501, para 1.7), an executive summary, the

analysis itself, supporting appendices and supporting documentation. (T-2).

1.3. Applying the Economic Analysis Approach: Overview.

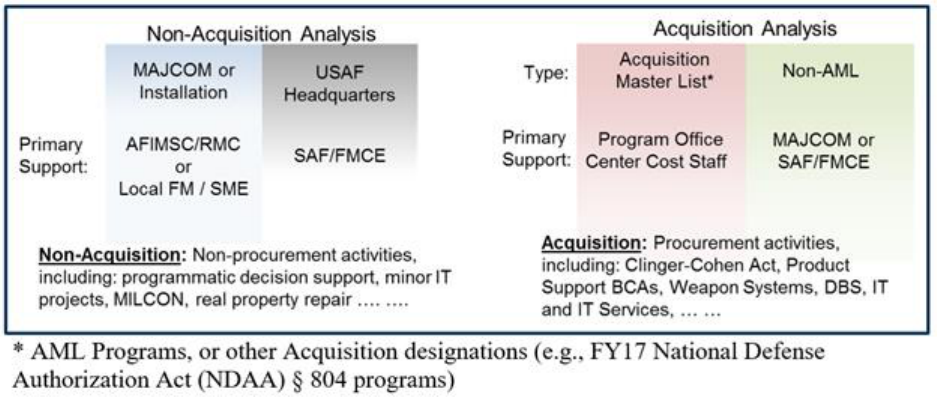

1.3.1. Sources of guidance and support

1.3.1.1. When the need for a comparative analysis is identified, one of the first questions

is where to get guidance and support. Figure 1.2 illustrates primary support organizations

for acquisition-related and all other analyses.

1.3.1.2. For Major Command (MAJCOM) and Installation organizations (outside of

weapon system acquisition), the Air Force Installation and Mission Support Center

Resource Management Cost Division (formerly the Financial Management Center of

Expertise) or MAJCOM Cost Staff are the primary sources of guidance and support.

1.3.1.2.1. The scope and type of project may affect which organization ultimately

assists with a comparative analysis project.

1.3.1.2.2. As an example, while an Installation Financial Office should contact the Air

Force Installation and Mission Support Center Resource Management Cost Division

for support with an analysis, that analysis may be passed to the Air Force Economics

and Business Management Division (SAF/FMCE) for support if its scope crosses

multiple MAJCOMs.

1.3.1.3. For Headquarters Air Force level organizations, SAF/FMCE is the primary source

of guidance and support.

1.3.1.4. For weapon system acquisition programs on the Acquisition Master List or other

Acquisition designations (e.g., Fiscal Year (FY) 17 National Defense Authorization Act

section 804 programs), the primary source of guidance and support is the program’s Center

Cost staff.

1.3.1.5. For acquisition programs which are not included under paragraph 1.3.1.4 above,

the primary sources of guidance and support are SAF/FMCE, MAJCOM Financial

Management staff, or Center Cost staff.

10 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

Figure 1.2. Comparative Analysis Support.

1.3.2. Build a Plan and Schedule

1.3.2.1. Build a plan for the analysis. Identify key personnel including the decision maker,

functional experts, and other analysts and support. Confirm the objective and scope of the

analysis and how it will be used. Identify sources for cost, performance, capability, and

other benefit and uncertainty data, etc., as applicable. Verify the higher-level review and

certification requirements. Identify the specific deliverables required.

1.3.2.1.1. Depending on the scope and the time available, hold a kickoff meeting with

key stakeholders to determine the plan and schedule.

1.3.2.1.2. The elements in this section are important to consider even for an analysis

which will not be formalized.

1.3.2.2. Timeliness is important in a comparative analysis. Particularly when there is a

hard suspense (e.g., Program Objective Memorandum build), it is important to develop a

schedule that meets the decision-maker’s timeline. If the analysis is completed too late for

the decision, it will not have an impact. When the suspense is softer, the analyst may be

able to negotiate the schedule in order to provide a more robust analysis. This is a balance

that will need to be addressed early in the program.

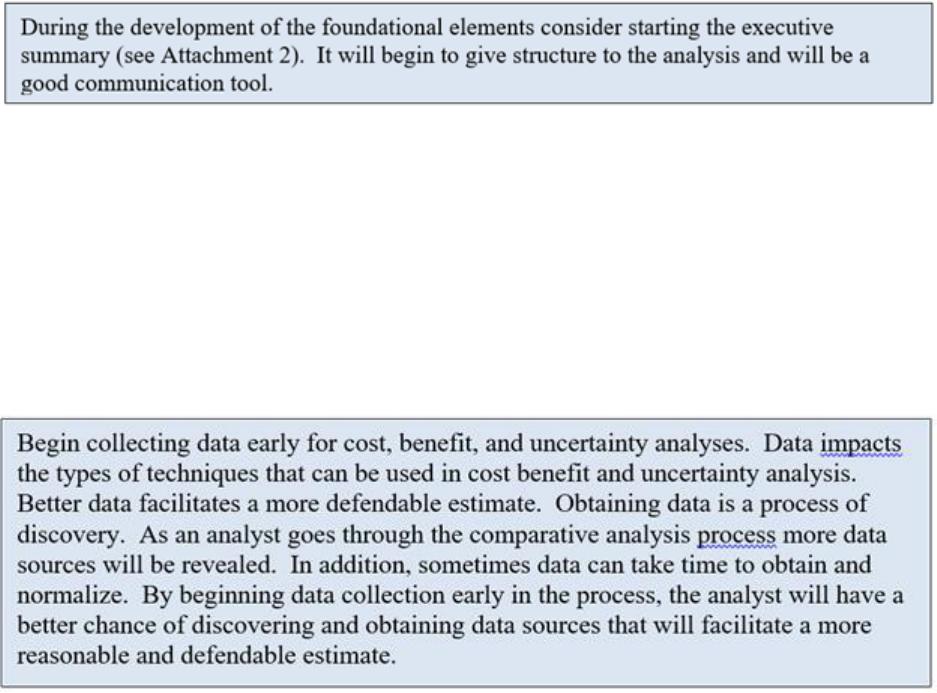

1.3.3. Foundation - Work with the requirement owner to develop foundational elements.

1.3.3.1. The foundational elements include: background, objective, scope, facts,

assumptions, and ground rules.

1.3.3.2. These foundational elements guide the remainder of the estimate. It is important

to understand that while they guide subsequent analysis, they can be revisited and updated

if the update would lead to a more valuable analysis. In particular, the assumptions should

be revalidated and updated during the analysis process.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 11

Figure 1.3. Foundational Elements.

1.3.4. Alternatives – After these initial steps, the analyst will have the foundation needed to

develop a set of alternatives that would satisfy the objective. Chapter 3 provides more details

on developing an appropriate set of alternatives.

1.3.5. Cost/Benefits/Uncertainty – The foundation, together with the alternatives, will enable

the analyst to begin building the cost analysis, benefit analysis, and uncertainty analysis. As

part of the uncertainty analysis, the analyst should test the strength of the results using

sensitivity analyses and may assess risk. See Chapters 4, 5, and 6 for more detailed guidance

on cost analysis, benefit analysis, and uncertainty analysis.

Figure 1.4. Data Collection.

1.3.6. Summary and Comparison of Alternatives – With completed cost, benefit, and

uncertainty analyses, the analyst will have sufficient information to compare the alternatives.

In addition to comparing the alternatives, the analyst interprets the results. Chapter 7 provides

additional information on this step.

1.3.7. Documentation/Report – The analyst will finish the comparative analysis product (i.e.,

the documentation for the economic analysis) for delivery to the decision maker. (T-2). More

information on documentation is provided in Chapter 7.

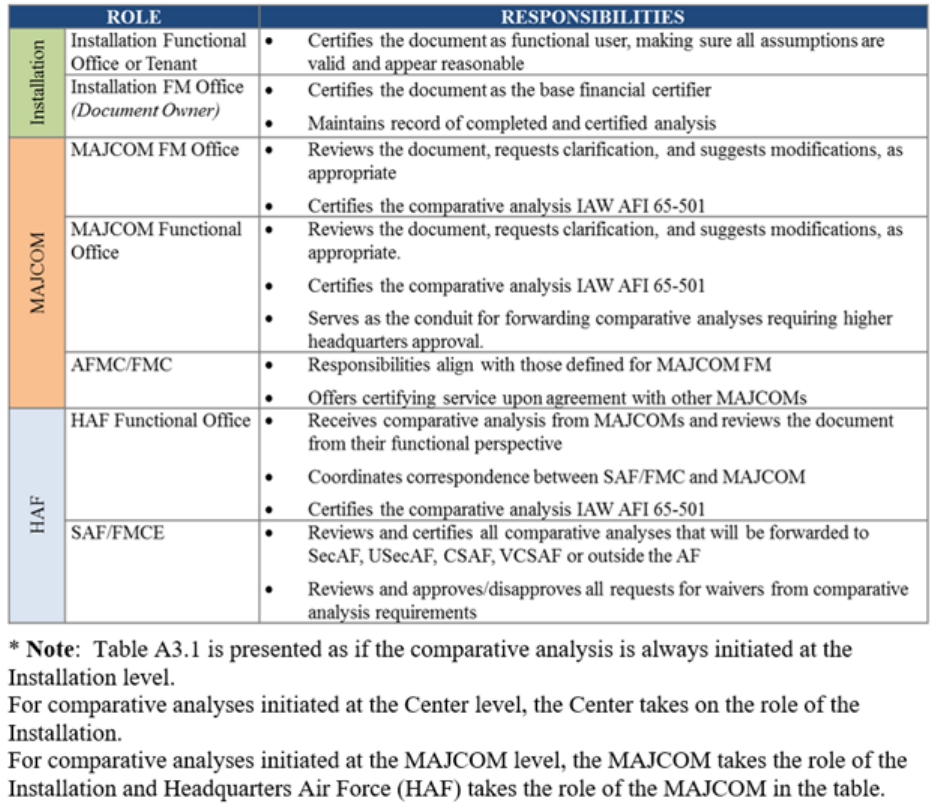

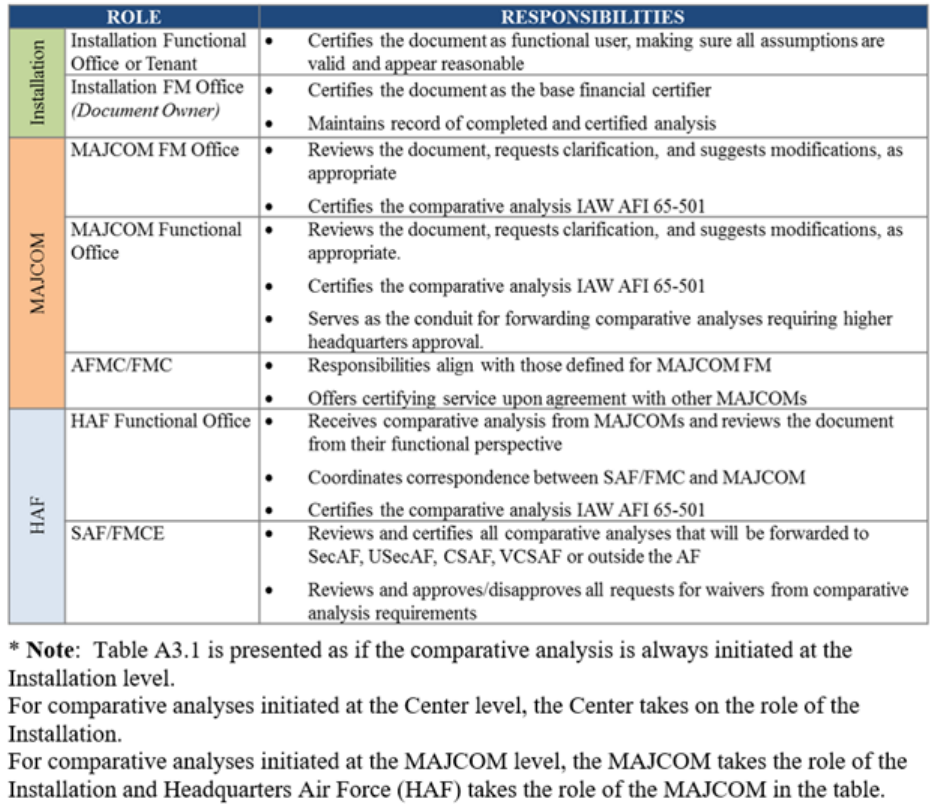

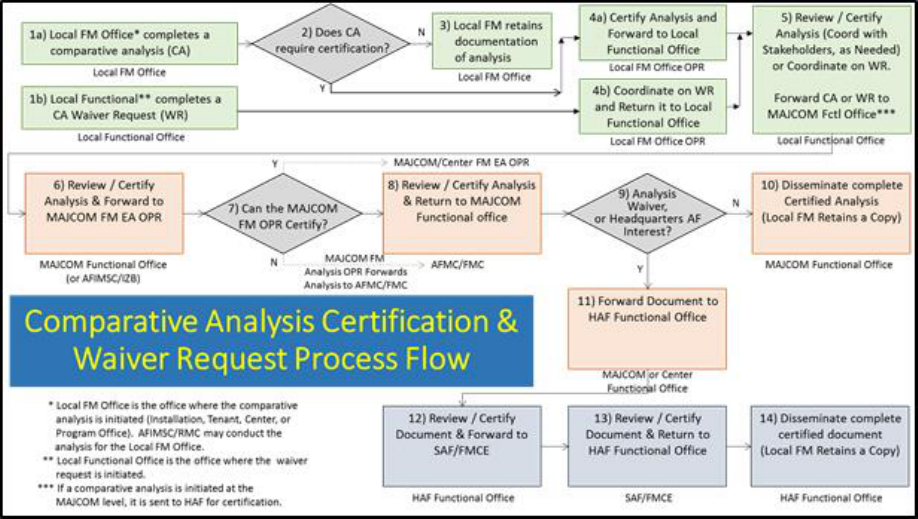

1.4. Roles and Responsibilities. For a complete listing of the Roles and Responsibilities of

developing an Economic Analysis, see section 1.4 of AFI 65-501. Roles and Responsibilities for

certification are contained in Attachment A3 of this manual.

12 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

Chapter 2

FOUNDATIONAL ELEMENTS: BACKGROUND, OBJECTIVE, SCOPE, FACTS,

GROUND RULES AND ASSUMPTIONS

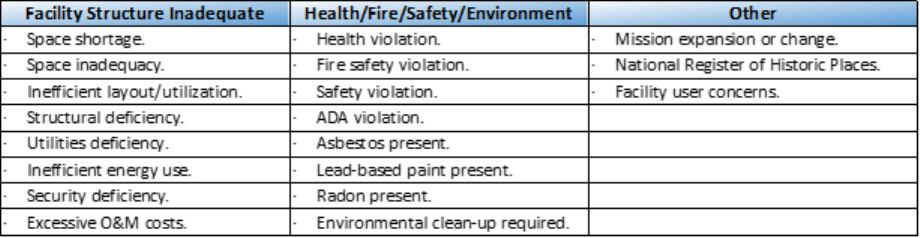

2.1. Background. The background provides a context for the analysis. The background should

be concise. Some examples of items to include in background context are:

2.1.1. A brief project/program history, technical description (if applicable), and current state

of the project/program. For a complex program, the technical description could include

information about the maturity of the concepts and technology.

2.1.2. A brief synopsis of why the analysis is needed (e.g., problem that is being addressed,

legislative compliance, Command directed).

2.1.3. Key milestone dates for the program, initiative, project, etc. that affect the timing or

constrain the scope of the analysis.

2.1.4. The intended audience for the analysis.

2.1.5. Timeframe for the analysis.

2.1.6. Any other relevant information on how the analysis will be used (budgeting,

contracting, etc.).

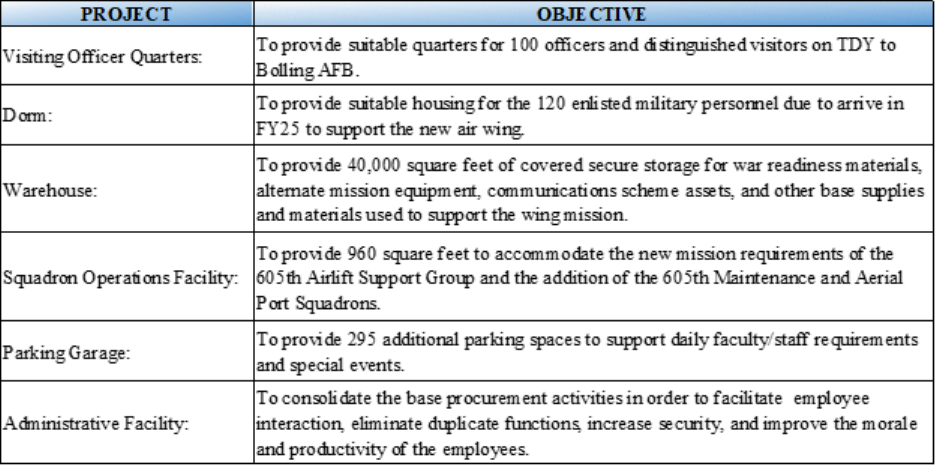

2.2. Objective of the Comparative Analysis. The objective of the comparative analysis is the

purpose for which the analysis is being performed. When doing the analysis, the analyst should

frequently reference the objective to ensure the analysis remains consistent with the purpose.

2.2.1. The objective statement should clearly and succinctly define and quantify, to the extent

possible, what the project or program under study seeks to attain (e.g., obtain sufficient

workspace for 200 people arriving on base as a result of gaining a new mission). It should state

the goal or objective (i.e., mission or mission support requirement) to be met by the alternatives

under study.

2.2.2. The objective should address the true problem to be solved. For example, do not limit

the objective to insufficient manpower at the gate to check IDs when the problem to be solved

is long lines (which may have a variety of solutions).

2.2.3. The objective should be stated broadly enough that it can be met by multiple alternatives

and not in a way that favors or pre-supposes one particular alternative. A narrowed objective

can sometimes introduce what is called pre-selection bias.

2.2.4. The objective statement should reflect the purpose of the project or program that is being

analyzed. Conversely, it should not be a statement of the objective of the analysis.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 13

Figure 2.1. Objective.

2.3. Scope.

2.3.1. The scope describes the content that is included in the analysis and the content that is

excluded from the analysis. In assessing the scope, the analyst will need to determine the level

of the objective (e.g., Society, Federal Government, Defense Department, Air Force,

MAJCOM, Installation, Portfolio, or Program). The scope is a focusing mechanism for the

analysis.

2.3.2. Be cautious of narrowing the scope unnecessarily. It is important to consider costs and

benefits, including potential second and third order effects, experienced by all affected

organizations.

2.3.3. Be cautious also of having a scope that is too broad or the analysis may become

unwieldy.

2.4. Parameters of the Analysis (Facts/Ground Rules/Assumptions). All parameters must be

explicitly stated. (T-2).

2.4.1. Facts - Facts are key parameters that will be significant to the analysis and for which

the value is known.

2.4.1.1. Facts may include information about factors that may be relevant for an analysis.

For example, in a vehicle lease versus buy analysis, a fact may be that there are currently

excess vehicles in the inventory.

2.4.1.2. An analyst should include important facts in the background of the analysis.

2.4.2. Ground Rules - Ground rules are general principles that provide bounds for the analysis.

2.4.2.1. Some common examples of ground rules include: period of analysis and type of

dollar used (base-year, then-year, and constant-year).

2.4.2.2. Ground rules can also involve the scope of the analysis. Certain areas can be

excluded from the analysis by ground rule. When doing so, the analyst should have a

rationale for the exclusion.

2.4.3. Assumptions - Assumptions are key parameters where the values and circumstances

must be estimated because their values depend on future events or there is a lack reliable

knowledge.

2.4.3.1. Only assumptions that are necessary and reasonable should be included in an

analysis. The reasonableness and validity of assumptions, as well as the need for new

assumptions, should be periodically re-assessed throughout the course of the analysis.

14 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

2.4.3.2. Avoid making assumptions where facts should be used.

2.4.3.3. Assumptions should not be made for the convenience of the analyst or one of the

stakeholders, or to unfairly favor one alternative over another.

2.4.3.4. The analyst should avoid treating assumptions as facts (e.g., past workload is a

fact, projecting that workload into the future is an assumption). Any such assumptions

should be explicitly stated in the Assumptions section of the analysis. Sometimes current

facts can be used as a foundation for an assumption. For example, the fact that there are

currently excess vehicles may be used to assume that the excess will persist in future years.

2.4.3.5. There are times when assumptions can appropriately narrow the scope of an

analysis to manageable proportions, but they should not unduly constrain the analysis by

eliminating otherwise reasonable alternatives.

2.4.3.6. Assumptions are one way to handle uncertainty in an analysis. A Sensitivity

Analysis must be performed to test the effect that major assumptions have on analysis

results. (T-1).

2.4.3.7. Examples of areas where assumptions are commonly made include: operations,

organization, facilities, schedule, discount factors, inflation factors, manpower factors,

production rates, utilization rates, workload, requirements and changes to requirements,

estimated economic lives, future events, efficiency factors and reliability rates.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 15

Chapter 3

ALTERNATIVES

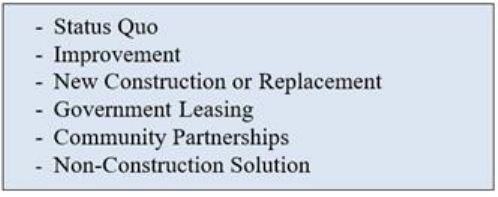

3.1. Overview.

3.1.1. Alternatives are reasonable courses of action to attain the stated objective.

3.1.2. In developing the analysis, the analyst will consider (identify and discuss) all reasonable

alternatives. All alternatives that are reasonable and feasible shall be fully analyzed. (T-2).

3.2. Baseline/Status Quo

3.2.1. Analyses almost always include a baseline alternative by which all other alternatives

are compared. Typically, the baseline is the Status Quo alternative. The baseline describes

how the program or process under study currently performs with respect to the objective.

3.2.2. If the analysis is on a new initiative, there may not be a baseline to measure against. In

some cases, the Status Quo may be infeasible or unreasonable. (See paragraph 3.3.4) In those

cases, another alternative, or modified status quo, is commonly set as the baseline in order to

have a comparison point for the analysis.

3.3. Reasonableness and Feasibility

3.3.1. The analyst shall address all reasonable alternatives. (T-2).

3.3.2. Each reasonable alternative shall be evaluated for feasibility. (T-2). Alternatives that

are reasonable and feasible shall be fully analyzed. (T-2).

3.3.3. If any reasonable alternative is deemed infeasible, the reasons shall be fully explained

in this section. (T-2). After documenting reasonable alternatives that are infeasible, the

infeasible alternatives do not need to be considered any further in the analysis. Documenting

reasonable alternatives that are infeasible alternatives informs readers and reviewers that all

reasonable alternatives were considered, and provides the rationale for deeming some

alternatives as infeasible. If there are alternatives that are feasible, but excluded for some other

reason, the rationale for exclusion must be explained in this section (e.g., see paragraph 3.4).

(T-2).

3.3.4. Care must be taken to ensure a difference in capability or other benefits is not construed

to mean infeasibility. Infeasibility means an alternative does not satisfy the required minimum

level of acceptable performance (see paragraph 5.4.7.1.2). Mere differences in capabilities

should be accounted for in the Benefits section. In the analysis, the decision maker can weigh

the difference in benefits against any cost differences. One common pitfall is to define the

objective too narrowly (see Chapter 2) such that the Status Quo cannot meet the requirement.

For example, the objective may be defined too narrowly such that a new business system is the

only alternative to meet that objective. Instead, a properly defined objective would allow for

the status quo, or a modification to the status quo to be feasible, but not provide as many

benefits.

16 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

Figure 3.1. Reasonable and Feasible Examples for Alternatives.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 17

Figure 3.2. Reasonable and Feasible Notional Illustration.

3.4. Completeness

3.4.1. Be thorough when developing alternatives. Make sure all reasonable alternatives are

included. It is essential to leverage input from key personnel identified in section 1.3.2.1 to

both identify and determine the reasonableness/feasibility of alternatives.

3.4.2. Use inputs from experts, critics, and supporters of various viewpoints. Be willing to

use external parties such as: the commercial sector, Congressional reports, or academia.

3.4.3. Consider combinations of systems or approaches and solutions that involve outside

agencies or organizations (e.g., community partnerships).

3.4.4. While considering a full range of alternatives, if the number of alternatives is too great

to be manageable, screen out the most unlikely in order to keep the number of alternatives to

a manageable level. Provide details regarding the down select methodology used.

3.4.5. Analysis is iterative, and as such, the set of alternatives may not be static. As the

analysis progresses and new information becomes available, be open to expanding or reducing

the set of alternatives.

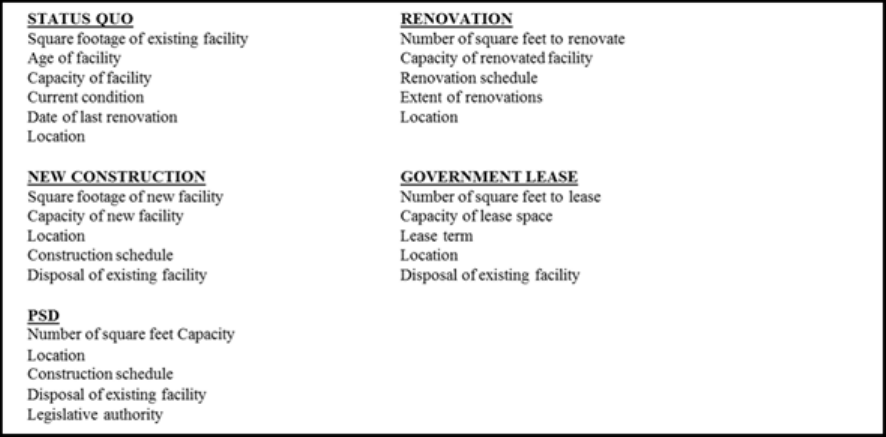

3.5. Describing Alternatives

3.5.1. Fully explain what each alternative involves, especially those aspects that are likely to

drive costs and benefits.

3.5.1.1. Explain how each process or procedure would work, what personnel, equipment,

or facilities would be required, and what other changes from the Status Quo or baseline

would be involved.

18 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

3.5.1.2. Each alternative should be fully described, to enable someone completely

unfamiliar with the program to fully understand what would be involved in its

implementation.

3.5.1.3. At a minimum, the description shall include attributes that will result in costs to

the government. (T-2).

3.5.2. When describing the alternatives, the analyst should not include conclusions about the

relative merit of the alternatives.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 19

Chapter 4

COST ANALYSIS

4.1. Overview - Cost Analysis

4.1.1. Cost estimates/analyses support many different types of decisions and activities. The

cost estimates in a comparative analysis are for the purpose of comparing the incremental costs

that would be incurred by the decision over the period of the analysis.

4.1.2. The cost analysis includes those items traditionally understood to be monetary costs,

revenues, and savings. As such, the cost analysis is really an analysis of monetary impacts

both positive and negative.

4.1.3. Cost methodologies must be thoroughly documented so the analysis can be replicated

if necessary. (T-2).

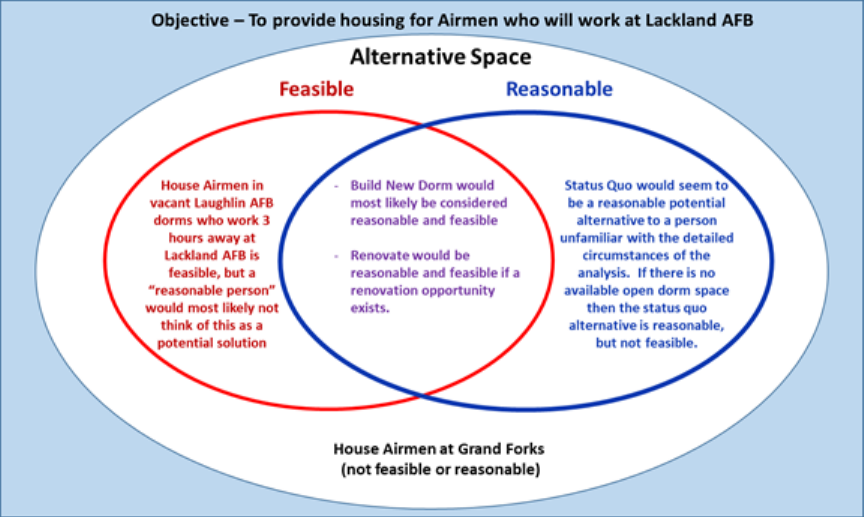

4.2. Purpose of Cost Analysis

4.2.1. The purpose of a cost analysis in a comparative analysis is different from its purpose in

many other uses. Key areas where the cost analysis of comparative analyses may differ from

other analyses include: the use of only incremental costs, the treatment of sunk costs, possibly

varying periods of analysis and treatment of revenue and savings (sometimes referred to as

monetary benefits). Cost analyses developed for another purpose need to be adjusted to

account for the difference in purpose in a comparative analysis. Some prominent purposes for

cost analyses and how they impact the cost calculations and presentation can be found in Table

4.1

Table 4.1. Cost and Purpose.

20 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

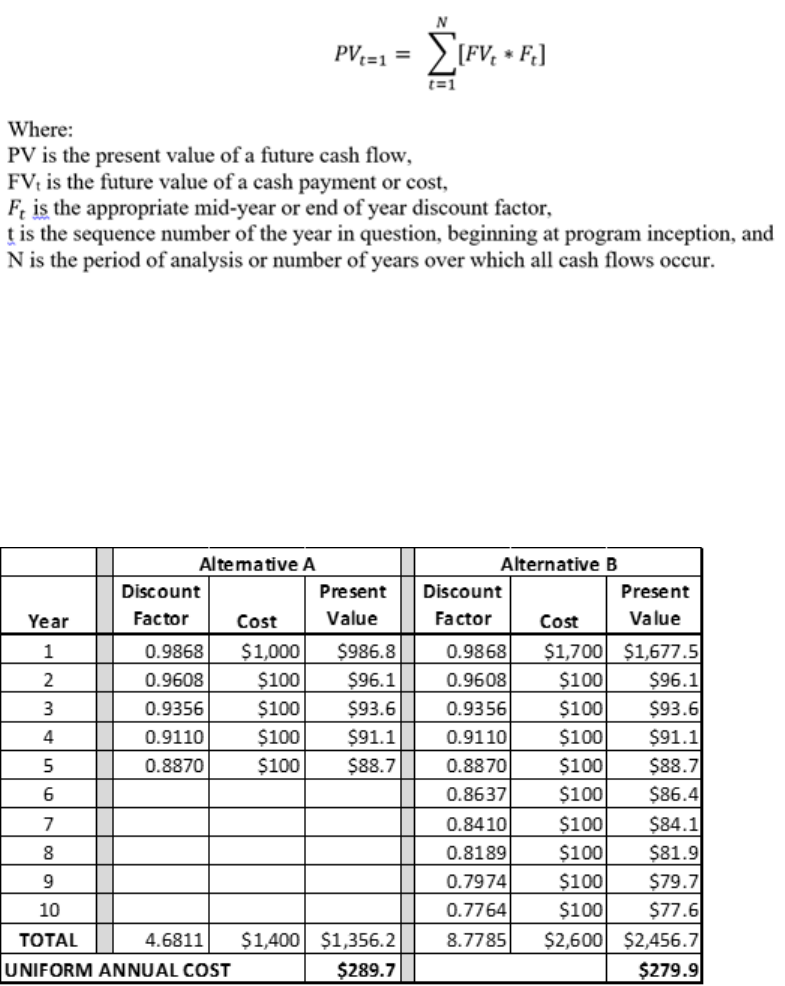

4.2.2. For comparative analyses, the cost analyses for the alternatives will be compared using

dollars that have been discounted to present value. (T-2). This allows for an appropriate

comparison of investment costs, typically occurring early in the period of analysis, with

recurring costs which typically occur later in the period of analysis. The year selected for

present value calculations is the first year investment funds will be required or the first year of

the analysis. This is commonly referred to as the base year of the program or project.

4.2.3. The estimate includes all costs incremental to the implementation of each

alternative.

4.2.3.1. Include incremental costs for those portions of the life-cycle covered by the period

of analysis. Include the cost of design, development, procurement, operation, support, and

disposal or residual value, as appropriate.

4.2.3.2. A comparative analysis normally includes all costs to the US government within

the scope of the analysis, not simply those incurred by the function under study. The scope

of the analysis should not be artificially drawn to exclude costs outside the Air Force.

While thorough cost analyses is the goal, it may not be possible to understand and capture

all of the effects a decision could have on other government agencies. The analyst will

have to use judgement to determine the extent to which costs outside the Air Force are

captured.

4.2.4. The cost analyses in a comparative analysis will only include costs for which funds have

not yet been expended or irrevocably committed. (T-2). In other words, sunk costs are not

included in a comparative analysis.

4.3. Basic Steps for the Cost Analysis

4.3.1. These steps are intended as a basic guide to developing cost analyses that fit within

economic analyses and the framework of this manual. These steps are not intended to be a

comprehensive guide to cost analysis. There are additional materials that provide more in-

depth guidance. Examples of additional materials include on-line Defense Acquisition

University courses (e.g., BCF130 Fundamentals of Cost Analysis), the Government

Accountability Office Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide, and the Government

Accountability Office Schedule Assessments Guide.

4.3.2. Review Foundational Elements

4.3.2.1. The cost analysis should be based on the objective statement and scope.

4.3.2.2. Reviewing the foundational elements will focus the analysis on the decision to be

made.

4.3.3. Build Cost Element Structure

4.3.3.1. The cost element structure is the framework for building the estimate.

4.3.3.1.1. The cost element structure is a hierarchical breakdown of the program or

project being estimated. Costs are estimated at the lowest level of the cost element

structure. The cost element structure (and the estimating technique used) will be

dependent on the data that is available. At times, the level of detail in the structure will

be limited because the available data better support a higher level estimating approach.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 21

4.3.3.1.2. It is important to understand the cost behavior of the cost elements when

building the cost element structure. For example, recurring and non-recurring should

not be included in the same cost element because the costs behave differently.

4.3.3.2. For a comparative analysis, each alternative may require different cost element

structures.

4.3.3.3. In many comparative analyses, a cost estimate for a particular alternative may

already exist. The analyst has to review the cost element structures across alternatives to

ensure the content included for each alternative is comparable.

Figure 4.1. Example - Build New Facility Cost Element Structure.

4.3.3.4. The latest version of the Military Standard 881 (MIL-STD-881) contains weapon

system related examples of work breakdown structures. Similarly, the Cost Analysis and

Program Evaluation Operating and Support Cost-Estimating Guide contains a cost element

structure for operations and support of weapon systems. While MIL-STD 881 and the Cost

Analysis and Program Evaluation Guide provide excellent examples, they may not fit the

circumstances of the alternative being estimated. As a result, the analyst may have to build

a new cost element structure to fit the level of detail and unique circumstances of their

estimate. Figure 4.1 contains cost elements that may be used in a facility construction cost

element structure.

4.3.4. Select Estimating Technique – will likely vary across cost elements

22 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

4.3.4.1. The estimating technique will depend on the data available.

4.3.4.2. The estimating technique can be different for each alternative and even each cost

element.

4.3.4.3. It is critical that the analyst ensure that the alternatives remain comparable even

when a unique estimating technique is selected for each alternative.

4.3.4.3.1. For example, an analogy-based estimate for one alternative may include a

computer hardware refresh because it was included in the analogous program.

Conversely, if another alternative was using an engineering estimate, the computer

hardware refresh may need to be estimated separately in a different cost element.

4.3.4.3.2. As another example, extrapolation of actuals is a common approach for the

Status Quo alternatives; while actuals are not available for new alternatives, the analyst

may employ a parametric model to estimate the costs of an alternative. Caution should

be taken to ensure that what is included in the actuals is comparable to the content of

the parametric model to avoid biasing the analysis in favor of one alternative due to

missing or overstated costs.

4.3.4.4. There are a variety of techniques that can be used to build the estimate. A list and

brief description of some common techniques are provided below. Training courses are

available with additional information on the estimating techniques. An example on-line

training course from Defense Acquisition University is BCF130 (Fundamentals of Cost

Analysis). The Government Accountability Office Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide

is also a valuable source for information on cost estimating techniques.

4.3.4.4.1. Analogy – Under this technique, the analyst estimates cost based on

historical data from a similar program. When using an analogy, the analyst should

include a technical comparison between the existing and proposed systems in order to

account for the difference between the analogous program and the program being

estimated.

4.3.4.4.2. Engineering (also called grass roots and bottom up) – Under this technique,

the analyst calculates labor and materials from the most detailed level of the program

and aggregates those costs to get the total program cost. While it is very detailed, this

method is generally more time intensive and includes a risk of missing some aspect of

the program when building the estimate.

4.3.4.4.3. Parametric – Under this technique, the analyst estimates cost based on

historical data from multiple past programs. Parametric estimates use cost estimating

relationships that correlate programmatic characteristics (e.g., size, lines of code,

weight) with cost. These cost estimating relationships can be developed either singly,

or as part of a software package. The analyst estimates cost using the programmatic

characteristics of the proposed program.

4.3.4.4.4. Extrapolation of Actuals – Under this technique, the analyst estimates future

costs based on historical data from the program being estimated. This technique can

only be used for programs that are on-going.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 23

4.3.4.4.5. Catalog Prices/Vendor Quote – This technique is simply obtaining quotes

from a vendor or catalog. This is commonly used to obtain a lease price in a

lease/purchase analysis. It is important that the analyst understand exactly what is

included in the vendor quote so that a proper comparison can be made across

alternatives. This technique works best with commercially available products where

multiple quotes can be obtained.

4.3.4.4.6. Factors – This technique is essentially a subset of the parametric technique

or the analogy technique. Essentially, a single factor can result from a cost estimating

relationship (e.g., Supervision Inspection and Overhead Cost as a percentage of

Construction Cost).

4.3.5. Collect Cost Data and Apply Estimating Techniques

4.3.5.1. Data collection should occur as early as possible because it may be difficult to

find good data. Similarly, data collection and the selection of estimating techniques is

normally be done simultaneously because the estimating technique depends on available

data.

4.3.5.2. As data is collected, use the selected estimating techniques to begin populating the

cost estimate.

4.3.5.3. Document completely the source/origin of all data collected. (T-2).

4.3.6. Time Phasing, Escalation, Inflation, and Discounting

4.3.6.1. Time phasing the estimate is ensuring that costs are placed in the year the cost will

be incurred. Proper time phasing requires that the costs be escalated to the appropriate year

using a price escalation index so that the estimate is in then-year dollars. The price

escalation index used must be documented. (T-2).

4.3.6.2. After the estimate is time phased and calculated in then-year dollars, the estimate

must be converted to present value dollars. (T-2). This can be done one of two ways. The

first way is to apply the nominal discount rate to the then-year dollars. The second way is

to first convert the then-year dollars to constant year dollars using an inflation index and

then use the real discount rate to convert the estimate to present value. Whichever method

is selected, the calculation must be documented. (T-2).

4.3.6.3. For detailed instructions on escalation and inflation, consult AFMAN 65-502,

Inflation.

4.4. Components of a Cost Analysis

4.4.1. It is important to understand what should be included in the cost analysis section of an

economic analysis. The cost analysis should only include the costs, savings and revenue

required as a result of selecting the alternative.

4.4.2. Sunk cost

4.4.2.1. Any cost incurred in the past, to include future costs that have been irrevocably

committed. An example of a future cost that has been irrevocably committed would be

work on a contract that has been performed, but not yet paid.

24 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

4.4.2.2. Such costs have no bearing on any decision to be made, and so should not be

included in a comparative analysis. Life cycle cost estimates will need to be adjusted to

remove sunk costs when being used for comparative analyses. (T-2).

4.4.3. Wash costs (also called Common costs)

4.4.3.1. Any cost that will be incurred identically across alternatives. Wash costs are

optional to include, but should be treated the same across alternatives (i.e., either included

or excluded) and documented completely.

4.4.3.2. Wash costs may be excluded for simplicity. This is sometimes called a “delta

estimate.”

4.4.3.3. Wash costs may be included so the decision-maker can get a full appreciation of

the magnitude of the cost of an alternative.

4.4.3.4. It may be necessary to include wash costs when using some estimating techniques

and data sources.

4.4.4. Average cost

4.4.4.1. The average cost is the total cost divided by the number of units that make up the

total.

4.4.4.2. When using these types of averages, make sure they are appropriate for the

analysis and will not bias the results. For example, the cost of a Captain in AFI 65-503 is

an average expected cost of all the Captains in the Air Force. If the study only involves

one location, it may be better to use the local Basic Allowance for Housing cost instead of

the average Basic Allowance for Housing listed in AFI 65-503.

4.4.5. Non-recurring cost

4.4.5.1. One-time costs or costs that are not expected to continue beyond the investment

phase. These costs usually take the form of initial capital or other unique expenditures.

4.4.5.2. Types of non-recurring costs include:

4.4.5.2.1. Research and Development Costs

4.4.5.2.2. Investment costs. These are costs associated with the acquisition of

equipment, real property, nonrecurring services, nonrecurring operations and start- up

costs, and other one-time outlays.

4.4.5.2.3. Costs of acquisition, rehabilitation, or modification of assets such as: land,

buildings, machinery, equipment, furniture and one-time computer software costs.

4.4.5.2.4. Temporary facilities/swing space.

4.4.5.2.5. Costs of plant rearrangement and tooling associated with the project.

4.4.5.2.6. Nonrecurring services received from others, both internal and external to the

Air Force.

4.4.5.2.7. Cost to cancel or terminate any existing arrangement that would result if a

different alternative were implemented.

4.4.6. Recurring cost

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 25

4.4.6.1. Recurring costs are cost that are incurred repeatedly.

4.4.6.2. Types of recurring costs include:

4.4.6.2.1. Annual recurring cost: A cost incurred every year (e.g., membership dues).

Recurring costs many times occur at time intervals of less than one year (e.g., utilities).

Commonly these costs are aggregated and treated as annual recurring costs.

4.4.6.2.2. Periodic recurring cost: A cost incurred in a period greater than one year

long, like Programmed Depot Maintenance, or replacement of heating, ventilation and

air conditioning equipment that may be replaced every 20 years.

4.4.7. Fuel/Energy Costs: The fully burdened cost of delivered energy shall be used in

analyses conducted for all Department of Defense tactical systems with end items that create

a demand for energy. (T-0). Be sure to only include those costs that are incremental to a

decision.

4.4.8. Induced Costs: Induced costs are those costs that the execution of a given project or

program alternative impose on another Air Force or government program. For example, if a

proposal to move an activity into facilities currently occupied by a second activity causes

expenditures by the second activity for real property acquisition or improvement, then those

expenditures are induced costs that should be taken into account in the decision to move the

first activity.

4.4.9. Costs incurred in foreign currency: The cost analysis portion of comparative analyses

will be performed in United States dollars. (T-1). See attachment 14 for additional details.

4.4.10. Opportunity cost

4.4.10.1. Opportunity cost is the cost of a resource measured in terms of its value in the

best alternate use. One way opportunity costs are accounted for in comparative analyses

is through the discount rate. Some projects may experience additional opportunity costs

specific to that project.

4.4.10.2. For example, the value of an existing asset may be included when there is an

opportunity cost associated with the asset. As an example, assume a piece of equipment

valued at $1,000 is being used in the Status Quo process. In the process for Alternative 1

the equipment is not needed; however, the same equipment was programmed to be

purchased by another organization. This other organization will be able to forego the

purchase and use the existing equipment if Alternative 1 is selected. In this case, the

equipment could be counted as a negative cost in the cost analysis for Alternative 1 because

the other organization now does not need to purchase the equipment.

4.4.11. Depreciation expense.

4.4.11.1. Depreciation accounts for the gradual consumption of capital goods and

resources over time. A common use is to allow business to "recover" investment in capital

goods through tax benefits.

26 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

4.4.11.2. Normally, depreciation will not be included as a cost in an Air Force economic

analysis since it would double-count expenses (i.e., the acquisition cost of assets are

entered when the asset is acquired). However, depreciation procedures can be used to

estimate terminal or residual values. Depreciation may be a consideration in commercial

lease versus buy alternatives if it provides extraordinary tax benefits to the lessor that are

a cost to the Treasury.

4.4.12. Savings

4.4.12.1. Savings are not typically identified as a separate cost element. Instead, they are

reflected as the reduced cost of an alternative.

4.4.12.1.1. For example, if four people are required for a task in Alternative 2 instead

of the five required for status quo, the analyst would include the cost of four people for

Alternative 2. This will show up as a lower cost (savings) for that alternative.

4.4.12.1.2. Continuing the example, if hours are saved from multiple positions, but a

position is not deleted (or re-purposed), then there are no savings and the cost should

be recorded as five people for Alternative 2. In this case, the reduced hours are

accounted for in the benefit analysis. This benefit is commonly referred to as cost

avoidance.

4.4.12.2. Generally speaking, an analyst should only show the cost of the alternatives and

not make a statement about savings.

4.4.12.2.1. Savings, when calculated, can only be calculated from a currently approved

(funded) program as the baseline. Although approved funding is limited to the Future

Years Defense Program, reductions reasonably likely to occur beyond the Future Years

Defense Program period are also savings because they are reducing cost for a program

or function that is assumed to be approved.

4.4.12.2.2. The status quo should represent the currently approved (funded) program

(plus extension beyond the FYDP). Sometimes, in addition to the status quo, an

analysis will contain a Status Quo Prime. One reason to include a Status Quo Prime is

to reflect a shortfall in funding. If this is done, the analyst should not leave the

impression that the resulting difference between Status Quo Prime and the alternatives

reflects savings. If an alternative were selected and executed, the amount between

Status Quo Prime and Status Quo would be cost avoidance and the difference between

Status Quo and the alternative would be savings.

4.4.12.2.3. If savings are calculated, they should be categorized into three time periods:

budget year, FYDP, and beyond FYDP. This structuring of savings allows for

recognition of the level of certainty of the funding.

4.4.13. Revenue

4.4.13.1. In the context of a Comparative Analysis, revenues are funds remitted to the US

government as a result of a service performed or good provided in one of the alternatives.

4.4.13.2. Revenue should be included as a “negative cost” in the cost analysis.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 27

4.5. Other Considerations in the Cost Analysis

4.5.1. Base year: Usually defined as the FY in which a program was/will be initially funded.

This will normally be the Start Year of the analysis. When reporting costs in constant dollars,

they should be reported in the dollars of the base year of the analysis. Do not confuse this Base

Year of Analysis with the base year of an Acquisition program, which is often set for the

Selective Acquisition Report at Milestone B.

4.5.2. Economic life: The economic life of a project or asset is the time during which benefits

from the project or asset may reasonably be expected to accrue to the Air Force. The economic

life of a project or asset is set by the shortest of its physical life, technological life, or mission

life. Economic lives of assets can often be found in functional area directives for planning,

programming, and budgeting for resources. Appendix 3 of Office of Management and Budget

(OMB) Circular A-76 also has a Useful Life and Disposal Value table.

4.5.2.1. Physical life: The number of years a facility or piece of equipment can physically

be used before it wears out.

4.5.2.2. Mission life: The estimated number of years that the need for the asset is

anticipated, before the mission either changes or is no longer required.

4.5.2.3. Technological life: The period before improved technology makes an asset

obsolete.

4.5.3. Period of analysis: Economic life plus project lead-time determine the period of analysis

for a comparative analysis. If the alternatives do not have equal lives, there are multiple

methods of selecting a period of analysis:

4.5.3.1. Terminal Value Method

4.5.3.1.1. The Terminal Value Method uses the terminal value or “salvage” value to

account for unequal economic lives of assets.

4.5.3.1.2. This method sets the period of the analysis to the duration of the alternative

with the shortest economic life.

4.5.3.1.2.1. The terminal and residual values of assets are included as inflows, or

negative cost amounts, in the final period cash flows for each alternative. This

adjusts the present value of the net cash flow for the disparity between the lives of

the alternatives. See section 4.5.8 for more information about the remaining value

of an asset at the end of its useful life.

4.5.3.1.2.2. To calculate the present value of each alternative under this approach,

the analyst needs to know the terminal or "salvage" values of the assets for the

alternative with the shortest life. For example, an engine replacement program may

plan to sell the status quo engines for scrap when they reach the end of their

economic lives.

4.5.3.1.2.3. The analyst also needs to know the residual values of the asset(s) for

the alternative(s) with longer economic life (lives). For example, an engine

replacement program would include the residual value of the replacement engines

when comparing those engines against the status quo.

28 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

4.5.3.2. Common Denominator Method

4.5.3.2.1. This method assumes the assets associated with each alternative are replaced

in the last year of their lives with identical equipment, and replacement continues until

all alternatives have assets reaching the last year of their lives during the same year.

Choose that year as the last year of the analysis.

4.5.3.2.2. It is important to keep in mind the major assumption being made: that

“chaining” the assets in this manner represents a realistic investment strategy. This

approach is not recommended for use with an asset having a short technological life

(e.g., computer hardware and software).

4.5.3.3. Uniform Annual Cost (also called Equivalent Annual Cost)

4.5.3.3.1. The Uniform Annual Cost method reflects a present value estimate of the

average annual cost for each alternative. In this method, the present value of the costs

are divided by the years in the economic life.

4.5.3.3.2. The period of analysis under Uniform Annual Cost is equal to the economic

life of the alternative with the longest economic life.

4.5.3.3.3. This method can be used in place of the Terminal Value Method.

4.5.4. Incremental Cost

4.5.4.1. The intent of this section is to better describe incremental costs, or the difference

in costs that will be expended between the base case (usually the Status Quo alternative)

and the other alternatives.

4.5.4.2. For each alternative, the estimate will include the incremental change in cost that

will have to be expended in order to execute the alternative being evaluated. The cost that

is included should be the incremental cost to the decision. In other words, only include

costs that will change as a result of the decision. (T-2).

4.5.4.3. Sunk costs and wash costs fit in the category of costs that are not incremental to

the decision.

4.5.4.4. Another category of costs that are commonly not incremental to the decision are

overhead costs. Depending on the magnitude change resulting from the decision, there

may be no change in overhead costs at all. However, if the change is large enough, then

there may be changes in infrastructure, base operating support, and other overhead that

need to be included in the analysis.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 29

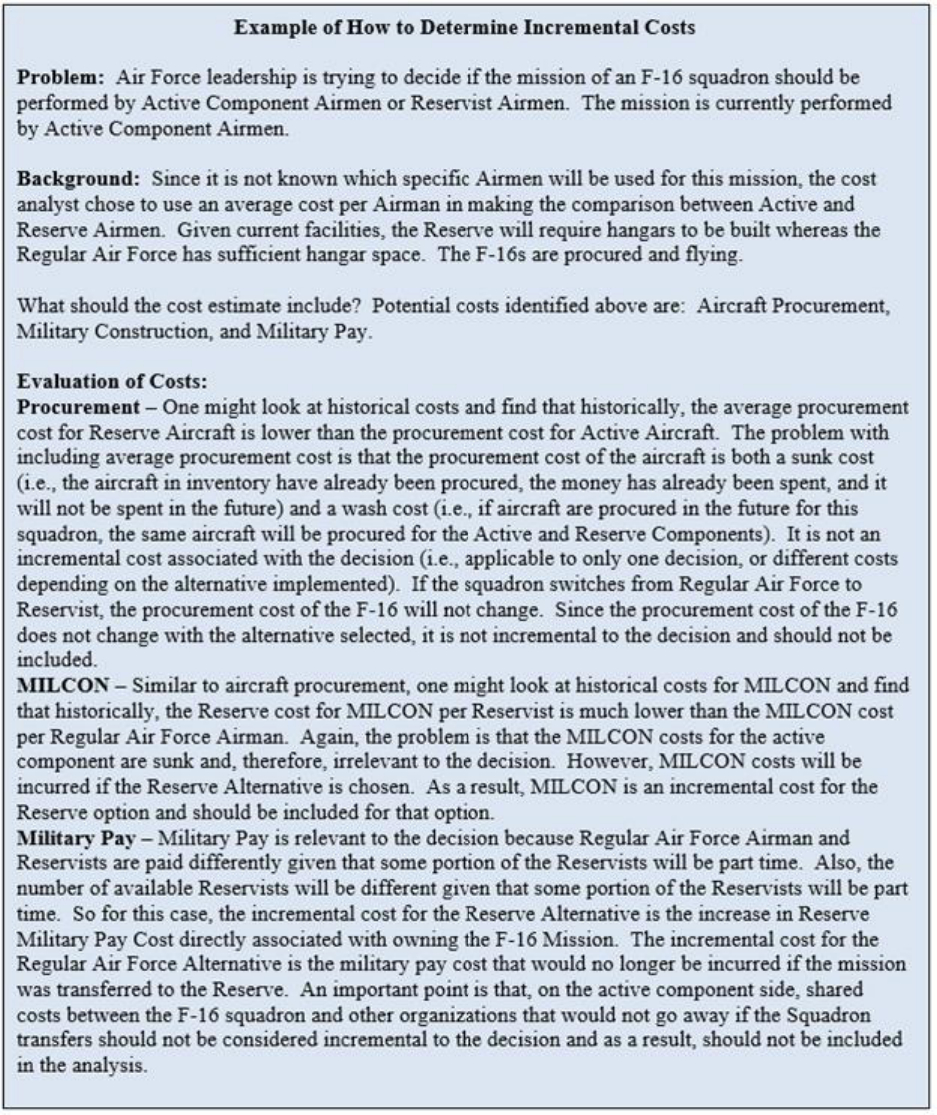

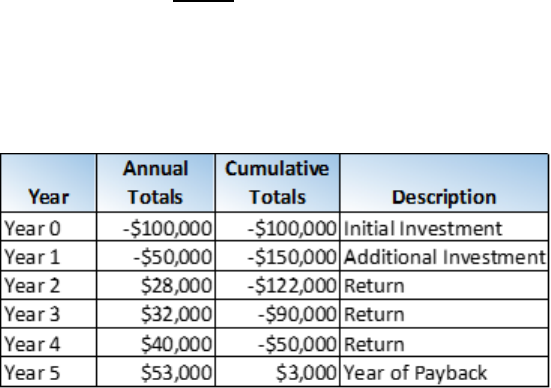

Figure 4.2. Incremental Cost Example.

4.5.5. Confidence Levels

4.5.5.1. If cost risk was assessed in the estimate for one alternative, cost risk should also

be included for other alternatives, where appropriate, and all alternatives should be

evaluated at similar confidence levels.

30 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

4.5.5.2. Common methods for assessing cost risk include:

4.5.5.2.1. Enhanced Scenario-based method: the analyst quantifies what can go right

and what can go wrong with a program/project from a high-level perspective (as

opposed to the more detailed level perspective common to simulation). The result

provides an estimated cumulative probability for the true program cost. More

information can be obtained from the Joint Agency Cost, Schedule, Risk and

Uncertainty Handbook.

4.5.5.2.2. Simulation is also used to evaluate risk in cost estimates. There are a variety

of software packages that can be used to assist with using simulation to evaluate cost

risk. Two common methods of applying simulation to cost risk are the Cost Informed

by Schedule Method and the Fully Integrated Cost/Schedule Method. More

information can be found on these methods in the Joint Agency Cost, Schedule, Risk

and Uncertainty Handbook.

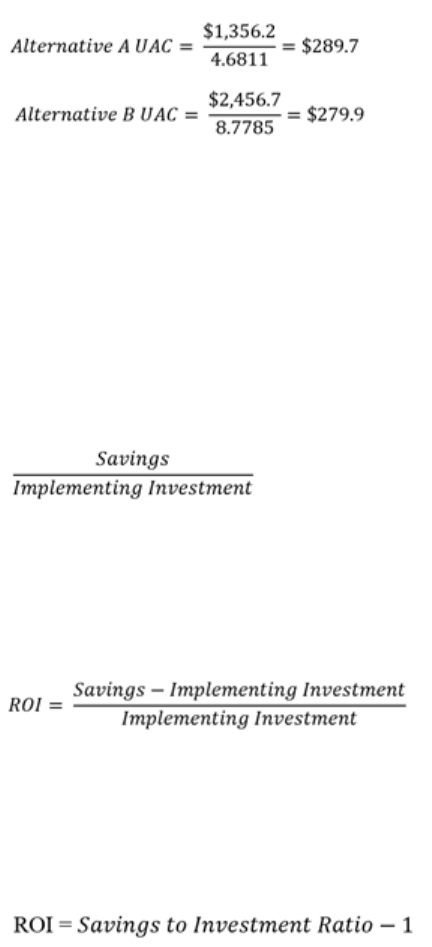

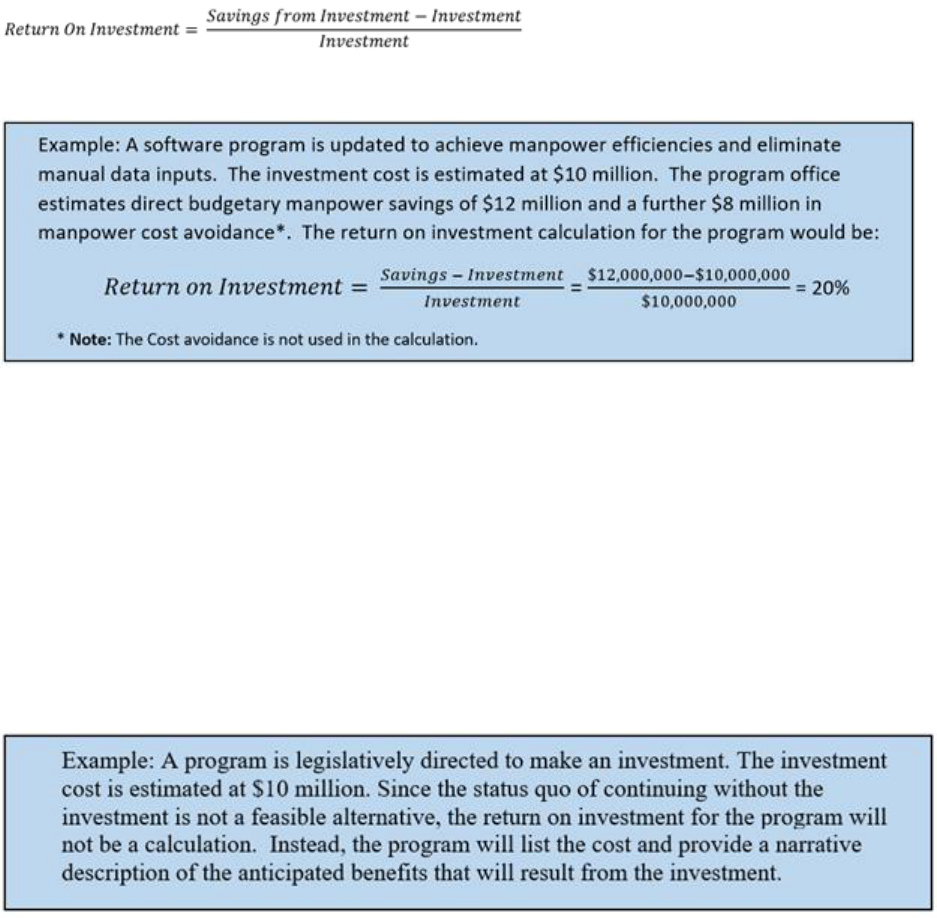

4.5.6. Monetary Benefits

4.5.6.1. Monetary Benefits include revenues and savings as defined in the glossary to this

manual. Monetary benefits are included in the cost analysis. This does not include benefits

that could be dollarized, but would not result in revenue or savings.

4.5.6.2. Benefits that could be dollarized, but would not result in revenue or savings should

be recorded in the benefit analysis as per paragraph 5.3.2.2

4.5.7. Discounting and Present Value.

4.5.7.1. Discounting is a method of calculating the value today (present value) of a future

cost or stream of future costs.

4.5.7.2. The Air Force evaluates decisions using present value dollars (discounted dollars).

4.5.7.3. Discount Rates – Discount rates are the rates used to calculate present value in a

comparative analysis. In order to simplify the present value calculation, the rates are

sometimes converted to discount factors. The simplification is that the present value can

then be easily calculated by multiplying the discount factors with the stream of dollar

values.

4.5.7.4. Where to find discount rates. Comparative Analyses are performed using discount

rates that represent the government's cost of borrowing, as provided annually in the

President's Budget and Appendix C to OMB Circular A-94.

4.5.7.4.1. Rates used for analysis are interest rates on Treasury notes and bonds with

maturities of 3, 5, 7, 10, 20 and 30 years. The rate to be used should correspond to the

period of analysis for the project. Projects with terms different from those listed should

use a linear interpolation. For example, a four-year project can be evaluated with a rate

equal to the average of the three-year and five-year rates. Projects with durations longer

than 30 years may use the 30-year interest rate.

4.5.7.4.2. Interest rates on Treasury securities are cited on both a real and nominal

basis. For an estimate in constant year dollars, use a real rate. For an estimate in then-

year dollars, use the nominal rate.

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 31

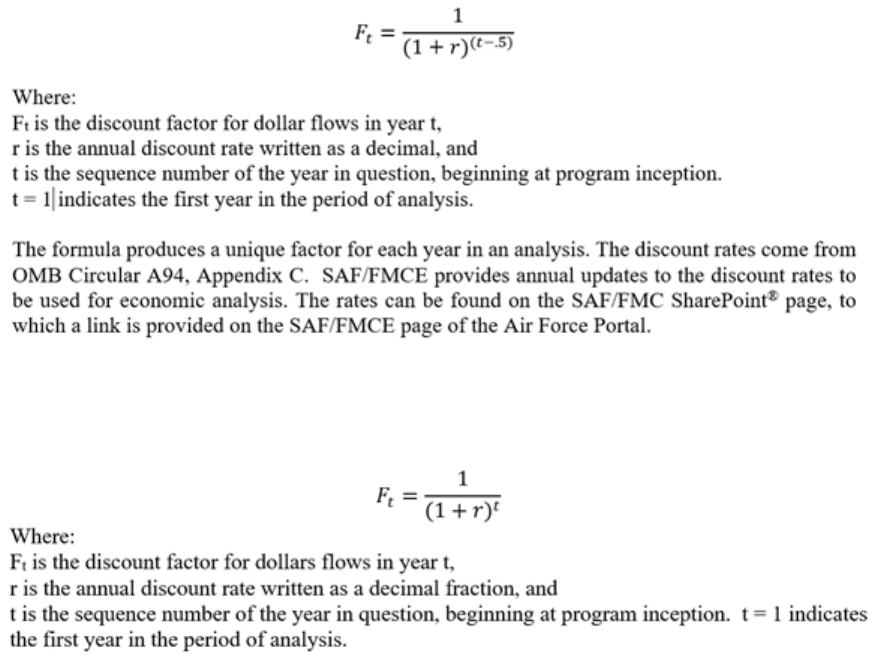

4.5.7.5. Discount Factors. Discount factors for use in comparative analyses are derived

from the discount rate used, using the formulas found in Attachment 7. There are two

kinds of discount factors that are common in Air Force comparative analyses.

4.5.7.5.1. Midyear Factors: When costs and benefits occur in a steady stream,

applying midyear discount factors is more appropriate. Midyear factors approximate

actual disbursement patterns--i.e., funds are typically disbursed throughout a given FY

rather than at its beginning or end. When the precise timing of outlays is critical to

program evaluation, monthly (or quarterly) rather than annual flows of funds may be

considered for early program years. Midyear factors should be used in Air Force

comparative analyses unless there is good reason to use other factors, in which case the

reason(s) should be explained in the analysis.

4.5.7.5.2. End-of-Year Factors: These factors implicitly assume that costs and benefits

occur as lump sums at year-end.

4.5.8. Remaining value at the end of an asset’s useful life (i.e., physical life, mission life, or

technological life).

4.5.8.1. The remaining values of assets are included as inflows, or negative dollar

amounts, in the final period of the cost analysis for each alternative. This step adjusts the

present value of the net cash flow for the differences between the lives of the alternatives.

A straight-line depreciation method is acceptable for estimating terminal, residual or

salvage value. This is done only to estimate the remaining value of existing assets, and for

no other purpose.

4.5.8.2. There are three terms used to describe the value of an existing asset that remains

at the end of its useful life: salvage value, residual value and terminal value.

4.5.8.2.1. Salvage value is the value of an asset at the end of its physical life (scrap

value). Salvage value is often offset by the cost to dispose of the asset.

4.5.8.2.2. Residual value is the value of an asset at any point in time before the end of

its economic life.

4.5.8.2.3. Terminal value is the value of an asset remaining at the end of its economic

life. If its economic life is deemed to be the same as its physical life, then terminal

value will equal salvage value. If, however, an asset’s physical life is longer than its

mission or technological life, there may be some value left in the asset beyond salvage

value.

32 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

Chapter 5

BENEFIT ANALYSIS

5.1. Overview – Benefit Analysis

5.1.1. An essential and critical element of an economic analysis is the consideration of

benefits. Without a consideration of benefits, the analysis is a cost comparison, not a

comparative analysis.

5.1.2. For the purpose of a comparative analysis, the benefit analysis section is generally

limited to non-monetary impacts. That is, the benefit analysis includes those aspects of the

alternatives that are not represented as a cash flow within the analysis.

5.1.3. There can be both qualitative and quantitative benefits and both types are important to

consider. Quantifying an otherwise qualitative benefit is useful for analysis, but does not

eliminate subjectivity. Weighting benefits is an important way to assess their relative value to

the decision.

5.1.4. All benefit elements that are analyzed should be fully explained so that someone

unfamiliar with them can fully understand the benefit and its measurement.

5.2. Role of Benefits

5.2.1. The purpose of benefit analysis is to identify, measure, and evaluate the benefits

provided by each of the proposed alternatives.

5.2.2. Since benefits reflect the performance of the organizational mission or service desired,

they are the primary reason for a project. While costs can be thought of as “inputs” to a project

or program, benefits can be thought of as the “output” or what the government receives for the

resources input. Considering benefits is essential to a comparative analysis. Benefits or results

are the reasons for the investment, but there can also be benefits that are ancillary to the

objective. These ancillary benefits can be recognized in the analysis, but should be secondary

to those benefits that are directly related to the project objective.

5.2.3. The selection of any particular alternative should be based on a full economic

evaluation, in which costs and benefits are appropriately weighed and compared. An

alternative with the lowest cost may not be the preferred alternative after costs and benefits are

considered together.

5.3. Types of Benefits

5.3.1. The benefits section focuses on non-monetary impacts. If implementing an alternative

would result in a reduced operating cost, then that reduced cost should be reflected in the cost

analysis, not the benefit analysis. Similarly, if one of the alternatives results in revenue to the

Air Force, then that should be reflected in the cost analysis, not the benefit analysis.

5.3.2. There are two types of benefits – quantitative and qualitative.

5.3.2.1. Quantitative benefits

AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019 33

5.3.2.1.1. Quantitative benefits are any benefits that can be measured quantifiably such

as a reduction in military man-hours. Characteristics like product or service

performance (e.g., miles/hour, orders/hour) or work environment (e.g., average noise

level, mishaps/week) often can be quantified. In such cases, these benefits should be

quantified to the greatest extent possible, and direct comparisons for each of these

measures across alternatives should be made.

5.3.2.1.2. Express these quantitative benefits in the units they naturally occur (e.g.,

military overtime hours, miles/hour) instead of converting the benefit into dollars.

Converting the benefit into dollars may mislead the decision maker into thinking that

such quantifications represent actual dollar cash flows.

5.3.2.1.3. Quantitative benefits in their unit, or raw, form should not be aggregated

across benefits. Since they are in different units, they should be presented as individual

benefits instead of an aggregated measure. If the quantitative benefits are converted to

percentages (e.g., 500 parking spaces out of 1,000 desired equals 50% of the desired

spaces) and weighted (see section 5.4.6), then they may be aggregated into a single

benefit score.

5.3.2.1.4. Cost Avoidance Benefits.

5.3.2.1.4.1. Cost avoidances are areas where someone may think the budget will

be affected when, in fact, it will not be. As a result, cost avoidance is accounted

for as a benefit.

5.3.2.1.4.2. There are two types of cost avoidance.

5.3.2.1.4.2.1. The first type of cost avoidance is productivity gains that do not

result in budget savings, such as man-hour savings that do not result in a deleted

position. Productivity efficiencies should be accounted for in their naturally

occurring metric (e.g., hours) instead of being converted to dollars.

5.3.2.1.4.2.2. The second type is a reduction in some future resource

requirement which: (a) has not been included in an approved (funded) Air

Force program or function within the Future Years Defense Program, and (b)

would not be reasonably assumed to be included in an Air Force approved

program beyond the Future Years Defense Program. This type of cost

avoidance benefit is the only benefit that should be measured in terms of dollars.

While the Air Force would not experience a reduction in funding from this

benefit, it represents the reduction in a potential liability. For example, if the

status quo anticipates the purchase of certain hardware which has not been

included in an approved and funded Air Force program, but implementation of

the preferred alternative does not require its purchase, there is a cost avoidance.

5.3.2.1.4.3. Cost avoidances can accrue at any time during the life cycle.

5.3.2.2. Qualitative benefits

5.3.2.2.1. Qualitative benefits are not naturally measured in quantities (e.g., mission

effectiveness, security, organizational morale). These benefits are usually subjective

in nature and generally do not lend themselves to quantitative analysis.

34 AFMAN65-506 6 SEPTEMBER 2019

5.3.2.2.2. There are techniques available which attempt to determine the comparative

desirability of each alternative with respect to each benefit and also attempt to measure

the magnitude of the differences in desirability between alternatives. While these

techniques do not measure qualitative benefits in an objectively quantitative way, this

approach allows us to establish a numeric basis of comparison. See Section 5.4.7 and

Figures 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4.

5.4. Basic Steps for Benefit Analysis

5.4.1. The steps for doing a benefit analysis are iterative in that the information gained from a

subsequent step may require the analyst to go back to a prior step.

5.4.2. Review Foundational Elements

5.4.2.1. The benefit analysis should be based on the objective statement and scope.

Reviewing the foundational elements will help keep the analysis focused on the decision

to be made.

5.4.2.2. The benefits developed should be benefits to the government within the scope of

the analysis, not simply those incurred by the function under study.

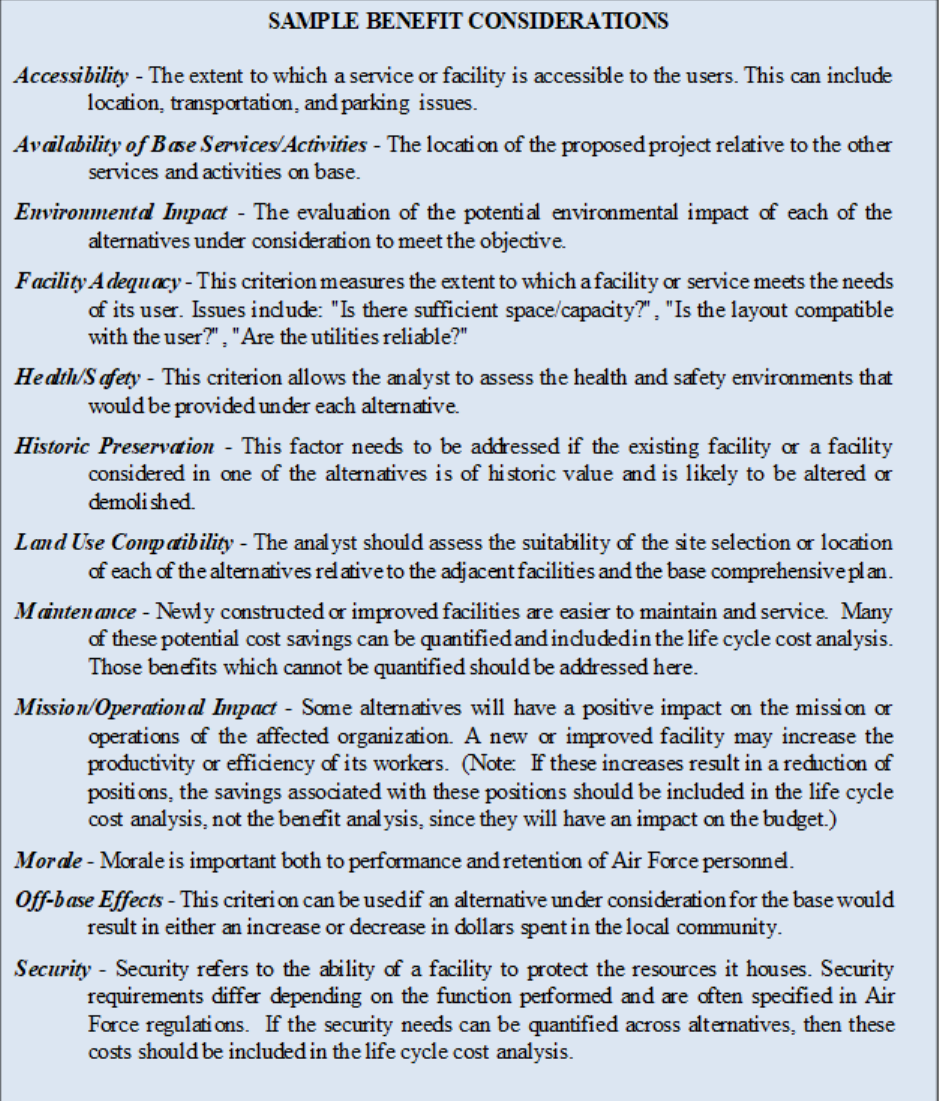

5.4.3. Identify Benefit Elements

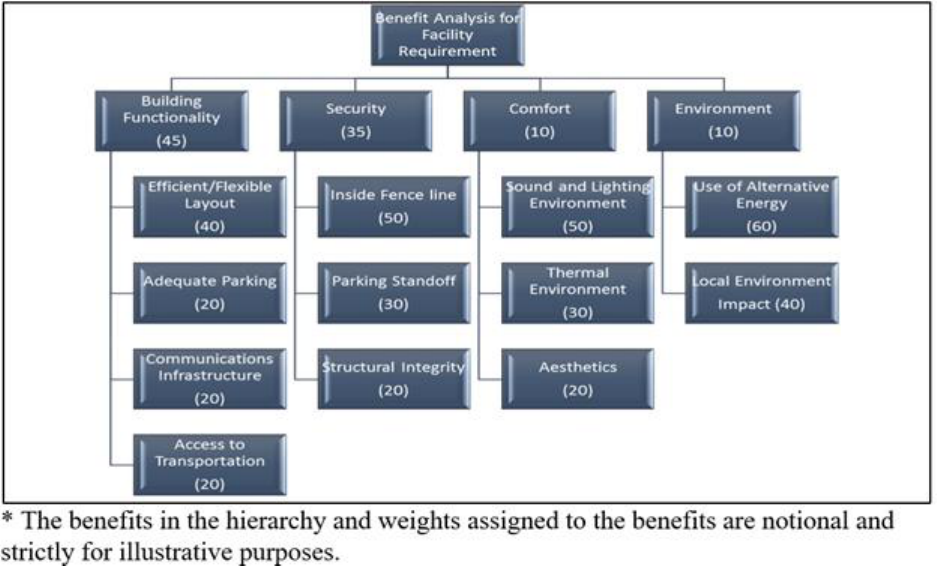

5.4.3.1. The benefit element structure is the framework for building the benefit analysis.

5.4.3.2. The benefit element structure varies depending on the analysis. Structures can

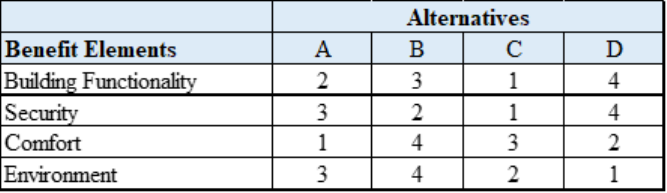

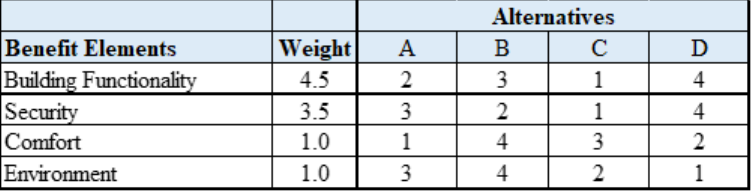

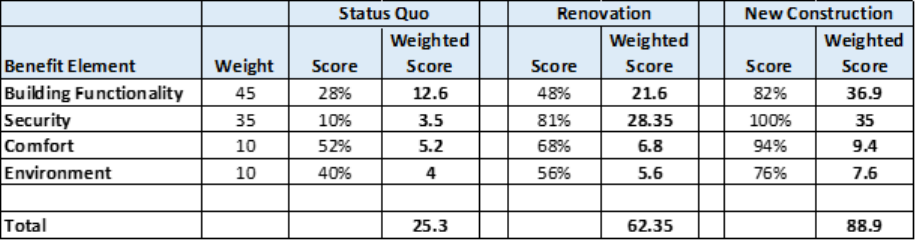

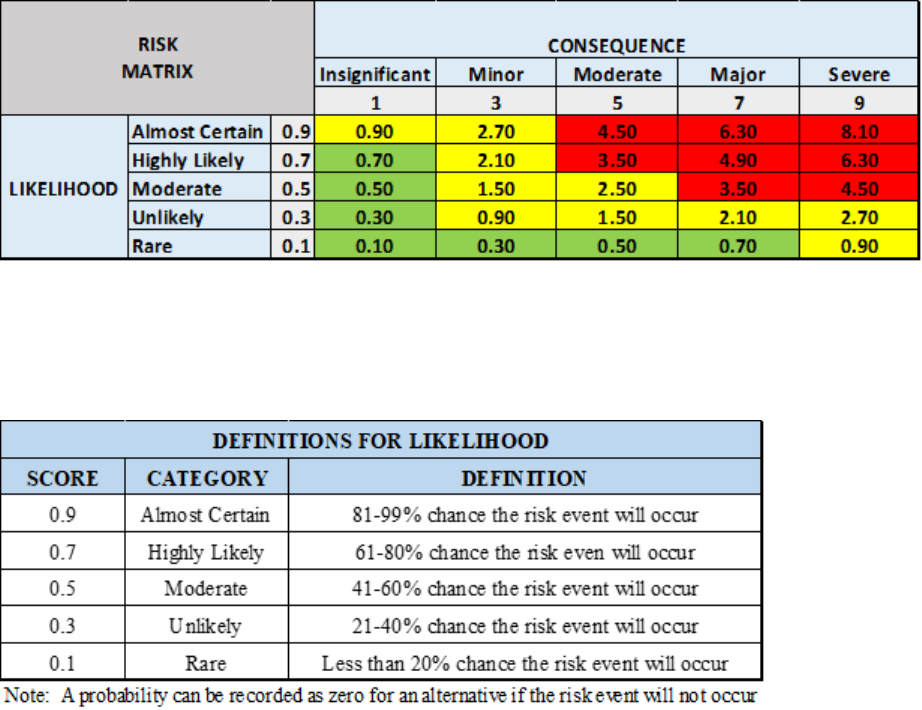

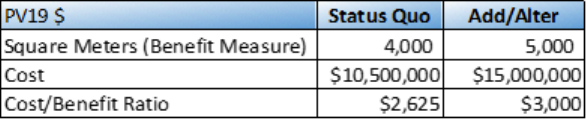

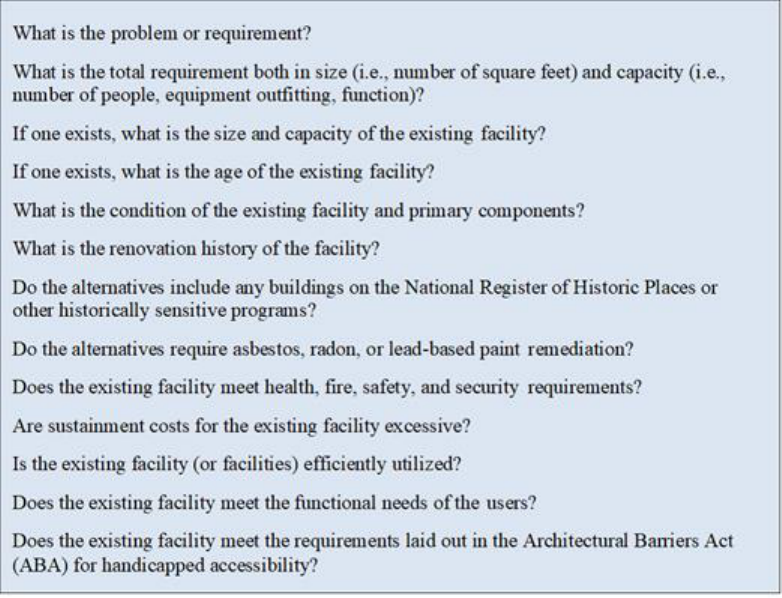

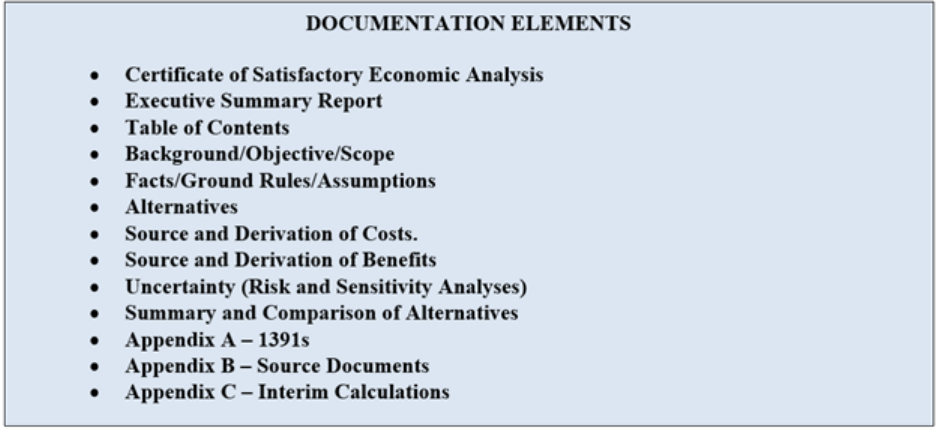

vary from a list of high level benefits to a hierarchical breakdown of the benefits for the